Baby Island Resort by Helen Scott, who, with her husband Darrel, owned the Baby Island fishing lodge.

I remember the early and latter days of South Whidbey with the clarity and nostalgia of one who lived them.

But most vivid of my memories is that area from Baby Island to Fox Spit. My husband pioneered and fished commercial in the days when Silvers were going for eight cents a pound in the 1920’s and early 30’s… And he trapped that shoreline for mink, weasel and raccoon in the days when a raccoon coat and cap were all the rage with the college set…

He built a fishing lodge on Baby Island. He could in no wise accommodate all who came. True stories of the fabulous fishing had spread, and it was not unusual to count over 200 small boats trolling on week-ends between Fox Spit and Baby Island, or spinning around the buoy. Salmon would strike at anything in those days. I recall my sister-in-law dragged a hand-line, and hook baited with a craw-daddy from our row boat and hooked a 31# salmon and a 34# Tom Cod.

Although the salmon runs dwindled to the rate of pollution in the rivers that killed the fingerlings returning to sea, many of the week-enders, enthralled by the beauty of the area, bought lots from a choice of plats and built permanent retirement homes, and they and their children’s family and friends continued to enjoy the recreational offerings of clam digging, crab dipping, bottom fishing, beach combing, duck hunting, and beach parties.

My ample years were enriched by the unspoiled blessings of God’s creation here and it grieves me to see it erode to commercialism. I can only pray that future generations will find some of these blessings preserved by a thoughtful society today.

Please forgive the errors. Father Time and eye surgery has taken its toll.

Fishing Derby, Johnson Resort. Caught between Baby Island and Bell’s Beach, 1941

Baby Island has a long history

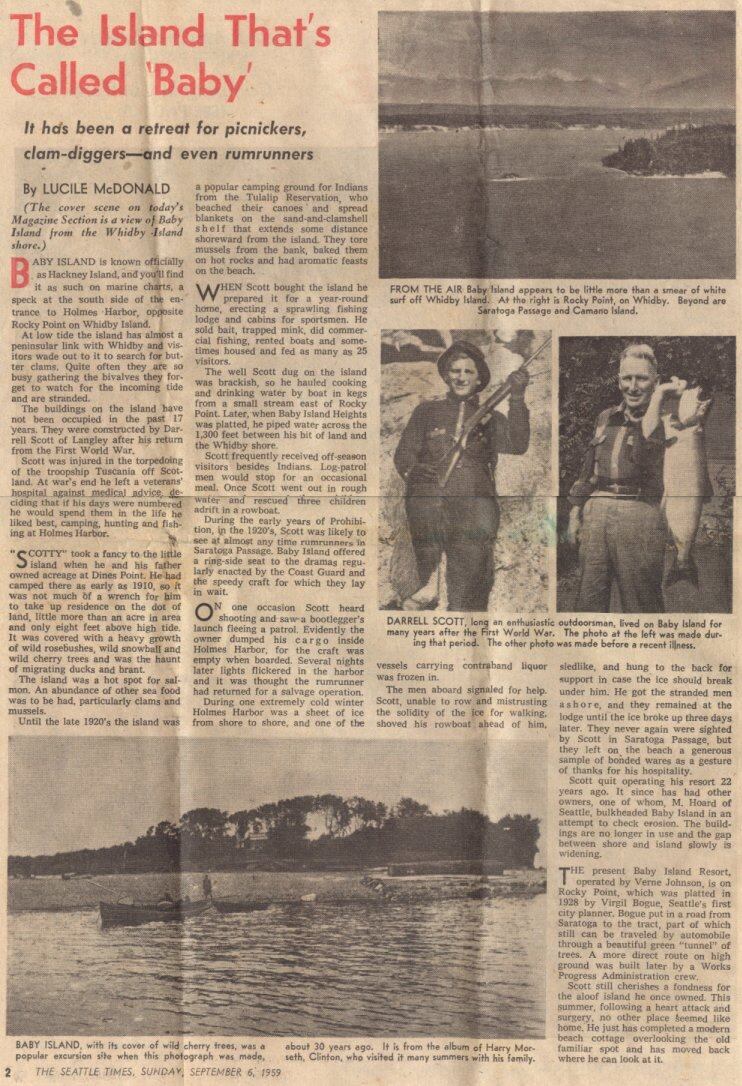

by Joan SoltysIn the 1920s, Baby Island was the site of a fishing resort built by Darrell Scott. At one moment it’s an island, a tiny dot of land in a large body of water, apparently inaccessible by anything but watercraft.

A few hours later, people, their dogs, even a mother with a baby stroller are approaching the small land mass on foot, walking up to it for a picnic, to fish from its shores or to dig some clams on the beach. Walking on water? No, just crossing the tide flats to Baby Island at a minus-low tide, when the water recedes enough to create a pathway to the land. It’s an intriguing phenomenon that has enchanted South Whidbey’s people for decades.

Baby Island, a small piece of land in Saratoga Passage, was once a gathering place for picnickers, fishermen, clam diggers and even rum runners. The Tulalip Indians traditionally had camps on both Baby Island and the land peninsula nearby. Lying at the south side of the entrance to Holmes Harbor and appearing on marine charts as Hackney Island, it doesn’t look very impressive now. Time and tides have taken a heavy toll, eroding away the land over the years. But in 1920, it was a solid acre of land sticking eight feet out of the water, covered with wild roses and cherry trees. That was when Darrell Scott of Langley bought the Island, and for a time it became a focus of activity in the area. It is quiet now, the buildings gone. There is no public access to the nearby beaches, and the island was purchased recently by the Tulalip Tribes. The Tribes permit local residents to still walk to the island and gather clams and mussels at minus low tides.

Walking to Baby Island takes only 10 minutes across the eelgrass and sand to the white strip of crumbled clam shells. Carrie Carpenter Anastasi, at a recent minus low tide, was pushing her double stroller to the Island. Her small twin daughters, Emma and Nora, were enjoying the ride and the adventure. Anastasi has a long acquaintance with the Baby Island. In her younger years, she would swim or kayak to the Island. “I even sometimes played with the seals, but I kept a cautious eye out for whales,” Anastasi said.

A few other visitors were paddling bright yellow kayaks, which they’d carried across to the island. We call ourselves the Baby Island Navy, joked Hal Doyle, a nearby resident who built the ingenious 20-pound kayaks. He was accompanied by Russ Johnson of Langley and Taylor Johnson, age 12. All three paddled around the island and then came ashore to the island for a quick lunch before the tide came in again. A fisherman sat quietly off shore in a small boat, and two families were headed back to land toting buckets filled with mussels and clams.

A solitary walker had a camera bag with him, and a few others brought their dogs along. Rhonda Jourdonnais and Terri Anderson were shepherding their canine companions as they returned to the mainland from the island. Trigger! Don’t roll in the seal poop! Jourdonnais called out to an Australian heeler. Also along were Laddie and Clancy (an Irish setter), both of whom were just as excited as Trigger about the abundant opportunities of the trek to and from Baby Island. On the island itself, there’s a small knoll, a place to picnic and maybe catch a glimpse of the seals that are prolific in the neighborhood. And there are still remnants of a few man-made structures to remind visitors that Baby Island was not always such a quiet, unpopulated little spot.

In 1920, young Darrell Scott saw development possibilities in this tiny bit of land. He was already aware it was a hot spot for fishermen. He had been an enthusiastic hunter and fisherman up and down Saratoga and Holmes Harbor during his youth. According to stories from long-time locals, Scott returned to the area after World War I as a way of healing. He purchased the island and built a home, a lodge and several cabins on the acre. (Depending on whom one talks to, the main building was referred to either as a casino or a fishing lodge.)

During the 1920s, bootlegging was fairly common in and about the waters of Whidbey, and Coast Guard boats constantly patrolled. Several stories are still told of Scott befriending more than one boat with a questionable cargo. Apparently, a boat owner’s appreciation for assistance would be generously expressed by leaving a supply of bonded wares on the Island’s shore. On one occasion, when Holmes Harbor had frozen over and a rum runner’s boat was stuck, Scott is said to have ventured out onto the ice to bring the crew back to his lodge until the ice melted.

For a time, Scott had to haul barrels of fresh water to his resort, but eventually he was able to lay a pipe from a small stream on the land out to his island. Luxuries such as electricity, phones and mail delivery were not available, however, until years later. Marge Rosenthal, a resident of Rocky Point on the mainland (across from Baby Island), said Scott’s lodge drew ardent sportsmen from Seattle, some of whom decided to build their own cabins on Rocky Point and along Holmes Harbor. They had names still familiar: Eddie Bauer, Gatch Coho, Virgil and Elizabeth Bogue, Percy Hodkins, Mildred and Ed Taylor and their sons, Vern Johnson and others who formed the first resident Baby Island Association. At that time, residents would row to Greenbank for supplies and the passenger steamer from Seattle, the Atlantic, would accommodatingly stop in the middle of Saratoga Passage and drop passengers over the side into a waiting rowboat, which then took them to the lodge or to a roughly built cabin where they could stay for $5 for a family (with $1.50 for an additional family).

Dependable road access didn’t come until the 1930s when the crews from the W.P.A. (Work Projects Administration) sawed, chopped and dug their way along the shoreline connecting Langley, Baby Island and Freeland. In 1937, Scott sold the island and built a home overlooking his beloved spot. The island passed through several more owners; one of them, M. Hoard, put in a wooden bulkhead to control the erosion, and a few of the logs are still in place. Continuing erosion finally forced abandonment of Baby Island. Some of the cabins were moved to Baby Island Heights and, with considerable modification, are still providing reliable housing. The buildings left on the island offered shelter of sorts for campers or an occasional hardy hermit-type until the early 1970s, when a heavy storm demolished all remnants of buildings and severely reduced the size of the little land mass, and Baby Island became what it is today — an island that, at certain times, you can walk to.

Here’s the article from the September 6, 1959 Seattle Times Magazine, about Baby Island. The article says that “during one extremely cold winter, Holmes Harbor was a sheet of ice, from shore to shore”. More Baby Island info can be found at http://www.oldcamano.net/babyisland.html

You can watch a wonderful video by Paul Shapiro on Baby Island’s history.