Our next newsletter, due out in early November, will feature information about Henry Bailey’s parents: Robert Bailey (South Whidbey’s first white settler) and Yabo-Litza (daughter of sub-chief S’Sleht-Soot (Peter) of the Snohomish Tribal village at Cultus Bay aka Digwadsh or D’GWAD’wk.

—————

STEAMBOAT CAPTAIN HENRY BAILEY MADE HIS MARK ON HISTORY…

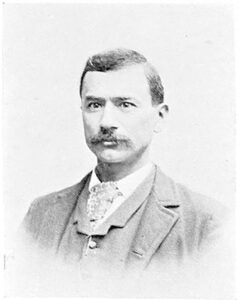

Born and raised at Cultus Bay on South Whidbey, Henry Bailey became one of the best-known and most respected steamboat captains during the heyday of the Mosquito Fleet.

Not only was Bailey a pioneering steamboat captain on Puget Sound, but he also made his mark on the Yukon River during the Klondike Gold Rush.

Henry’s father, Robert S. Bailey, was South Whidbey’s first land-owning white settler. Setting out from Virginia, Bailey arrived in what was then Oregon Territory in November 1851. (WA Territory would not be created until 1853.)

He took out an Oregon Donation Land Act claim of 162.5 acres that was adjacent to a permanent Snohomish Tribe village called D’GWAD’wk. (An article about Robert Bailey will be published in our next newsletter.)

Though primarily a farmer, he also operated a trading post and served as an Indian sub-agent. At Cultus Bay (called Bailey’s Bay for a time) he set down roots and married according to local tribal custom.

Robert Bailey’s first wife, Yabo-Litza, was born at D’GWAD’wk in 1840.

Her father was S’Sleht-Soot (English name Peter), one of the Snohomish Tribe sub-chiefs.

Her five uncles were also sub-chiefs and included: Snah-talc, an important sub-chief known as ‘Napoleon Bonaparte’ and Wha-cah-dub, who was the grandfather of William Shelton, the last hereditary chief of the Snohomish Tribe. (Shelton grew up at Possession Shores.)

As a sub-chief’s daughter, Yabo-Litza was ‘high-status’ or ‘high-born’ and was expected to marry outside of her village as a way of ensuring friendly relations and trade. As was typical of that time, she married young, at age 14 or 15. Tribal marriage custom was an exchange of gifts.

On August 5, 1855 Yabo-Litza gave birth to Henry E. Bailey, and three years later a second son, Robert F. Bailey. She would not see them grow up however, as she died in 1860 at age 20.

When Henry was 15, his father’s new wife, Charlotte Ladue, (also about 15 years old and a Snohomish Indian) gave birth to his half-brother, Nathaniel.

By the time that Charlotte gave birth to daughters Laura (1874) and Clarissa (about 1875), Henry had apparently left South Whidbey to find work, as he was no longer listed on the local census.

As a young man living at Cultus Bay, Henry must have given thought about his future. Should he become a farmer? A logger? A fisherman? Seek work at bustling Port Townsend?

Or perhaps he longed for a life of adventure on the maritime highway. Sailing vessels such as sloops and schooners and barks were increasingly being replaced by nimbler steamboats.

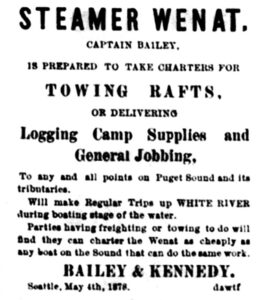

Henry got his start on the steamboat J. B. Libbey in 1875. In time, he would captain most of the steamboats that plied the Sound and nearby rivers; steamboats with names such as the Zephyr, Wenat, Fairhaven, Skagit Chief, and State of Washington.

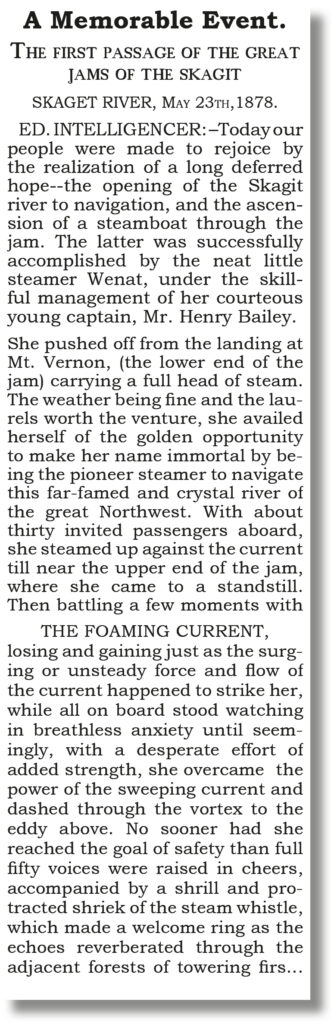

Bailey even made the newspapers in 1878 just after the massive logjams on the Skagit River were finally cleared.

‘Courteous young captain Henry Bailey’ piloted the sternwheeler Wenat upriver to a cheering crowd. (See attached article.)

He continued on the Wenat, but only a short while, for later that year she hit a snag and sank for the fourth time. (Steamboat crews often faced dangers from storms, fires, explosions, and collisions with rocks, logs or other boats.)

The Wenat’s salvaged boilers and engine were put into a steamboat called the Josephine.

Henry’s younger brother, Robert F. Bailey, started working as a fireman (loading cordwood to heat the boiler) on the steamer Josephine in 1879 when he was 21 years old.

Three years later, he was serving as acting Captain when tragedy struck Jan. 16, 1883. (The regular Captain and owners were signing legal papers at Port Townsend.)

Here is an account of the explosion that happened: (written by Phil Dougherty for the website HistoryLink www.historylink.org/file/804)

The Josephine left Seattle at 6:30 a.m. and proceeded north through Puget Sound. It was, “on the whole, a disagreeable day… being sloppy underfoot, and snowing some in the morning” (Seattle Daily Post-Intelligencer, Jan. 20, 1883), with the temperature a few degrees above freezing. By noon, the boat was between Mukilteo and Hat (Gedney) Island, approximately one mile offshore.

…Captain Robert Bailey relieved engineer Dennis Lawler in the engine room, and Lawler went upstairs to eat. According to the Post-Intelligencer, only an “ordinary stoker” replaced Lawler in the engine room, although Lawler claimed to have checked the boiler before he left: “Before going up I went to the boiler, and the gauge indicated 90 pounds of steam, and the glass was half-full of water” (Seattle Daily P-I, Jan. 17, 1883).

At about 12:05 p.m., the boiler exploded. Deckhand Frank Murphy, described what happened: “The gong had just sounded for dinner. The engineer had been relieved by Captain Bailey, and had gone upstairs to eat. The steamer was about a mile from shore, just off the ‘potlatch house’ [a log longhouse capable of holding some 200 people], at a large Indian camp at Port Susan, when all of a sudden, a terrible explosion occurred, which sounded like 49 cannons, all firing at once.

The crown-sheet [a part of the boiler] passed directly up through the pilothouse, and carried Johnson, the deck-hand at the wheel, far off into the air. The steamer immediately split in two, and the portion containing the boiler sunk in 30 feet of water. The cabin and a portion of the hull floated. The scene was terrible and indescribable.

The wounded women and men were groaning and crying, and the uninjured were rushing frantically around the wreck, not knowing which way to turn” (Seattle Daily P-I, Jan. 17, 1883)…

***

Fifteen people were rescued, however 8 people died, including Bailey, whose body was never found. It was the worst steamboat disaster on the Sound up to that point.

An inquest determined that the boiler had gone dry, which caused the explosion.

In 1879 Henry married Clarissa Hamblett of San Juan Island, who like him had an indigenous mother and white father. (Though listed on some census records as white, Henry was proud of his Snohomish Tribe heritage and filed tribal enrollment papers in 1918, as did his half-sister Laura Bailey Jewett.)

In 1887, Captain Bailey was the skipper of the Skagit Chief, with a stop at Clinton on Saturdays. He then became captain of the steamer State of Washington in 1889, so named when WA Territory became a State.

He must have passed his childhood home at Cultus Bay quite frequently over the years on his many runs.

North to the gold fields…

From 1893 to 1897 the United States was in an economic depression. What hit the Mosquito Fleet harder, was a new railroad which ran along the Sound coastline, significantly cutting the need for moving freight by steamboats.

Little towns along the coast, including Langley, were drying up for want of work that the steamers brought.

Then gold was found in the Klondike and the economy went from bust to boom almost overnight.

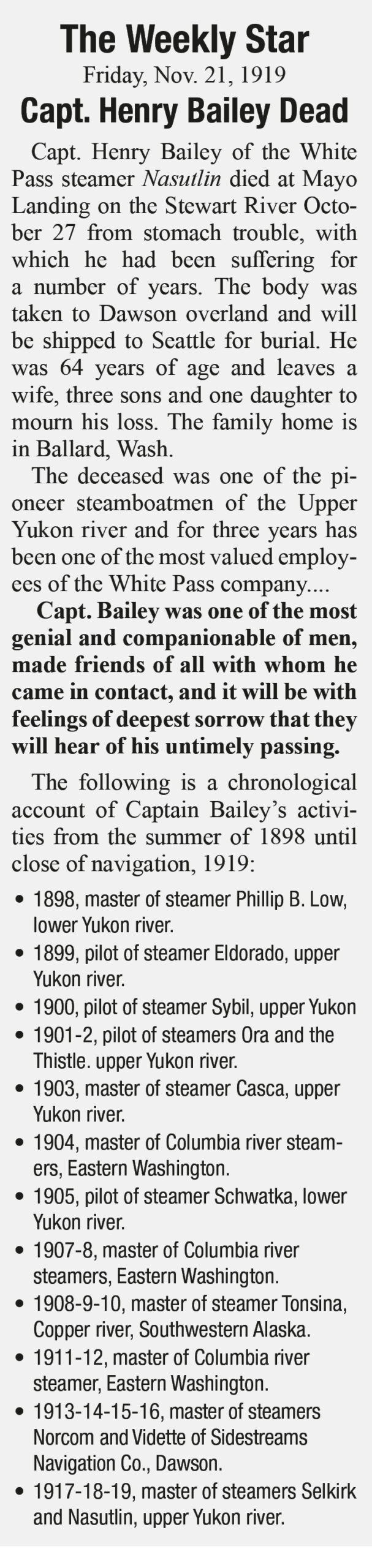

After 20 years captaining steamboats on the Sound and nearby rivers, Bailey signed on with the Klondike Corporation Ltd. and later the White Pass Company in Canada.

In 1898, he was in command of the Philip B. Low, delivering government supplies to Fort Selkirk at Dawson City in the Yukon Territory.

Though in ill health, Henry Bailey continued working until ice forced his steamboat to pull in at the silver mining town of Mayo in late October 1919. It was there that he died. He is buried at Mount Pleasant Cemetery in Seattle.

(This is an example of articles that you support when you become a member of the South Whidbey Historical Society and/or make a tax-exempt donation to the Society. Thank you for supporting our efforts of sharing our South Whidbey History.)