In his own words…

“I was born at Port Stanly in the Falkland Islands September 8, 1886. When I was two months old my father, mother and eight children came to the United States on a sailing ship which took three months from the Falkland Islands to New York via Portugal, Spain, France, Germany, and England.

We settled in 1887, near Cottonwood, Minnesota. This was near a small lake where the Sioux Indians used to stop and camp near our home once or twice a year on their journey to and from Pipestone Minnesota. There they got pipestone to carve pipes and other items to sell to the whites. My memory of them was of a very friendly people. My father was much interested in talking to them and trying to find any similarity in their language and the Patagonians.

I recall visiting in their teepee with my father and watching the Indian woman cooking something in a pot over an open fire and hoping father would leave soon, as one had heard that they ate dogs and skunks. They often stayed a week or more, and my brothers and sisters and I played with their children. When they would leave camp my brother often picked up pieces of pipestone of which I still have a piece. My father had them shell corn and gave them a meal for their work. The women would always gather up what food was left and take it to their papooses.

Father had intended to raise sheep. He bought three hundred sheep but the first winter the deep snow caved in the straw-roof shed and killed all the sheep.

When I was twelve years old I came to Washington State with my parents and three sisters and two brothers on an Immigrant Great Northern Train.

We arrived in Everett on March 24, 1899, and moved to Langley two weeks later on the stem wheeler steamboat Fairhaven.

We left Everett at 2 p.m. on a Tuesday and arrived at Langley 2 p.m. the next day. The steamer did not stop at Langley going north but stopped at all the logging camps on Camano Island and arrived at LaConner that evening where she tied up until the next morning. It was a wonderful experience for us children who had never been on a steamer. We had staterooms and meals were served aboard.

Father had bought five acres of uncleared land and a small house in Langley. He had an acre cleared for a hundred dollars, and he, my brother and I cleared the rest by hand.

Our first visitor was an old Indian squaw with a large salmon. A ten or twelve pound salmon sold for 25c (two bits). She told father the price was two bits. Father, not knowing what two bits was, offered her two nickles. She refused. Father then put two dimes in her hand, and she again said no, two bits, but took the money. She left but returned the next week with her husband leading her by about twenty steps. As soon as he was within hearing distance he yelled, “Two bits – a quarter – 25c.’’ That was how we first knew what two bits was.

My first job was picking prunes for Jacob Anthes who owned most of Langley and had a large prune orchard and a prune drying plant. We were told to bring any cracked or bruised prunes. He would dump them into a barrel and make prune “Jack” which he sold to the Indians. He was the Postmaster and had the only grocery store in Langley.

I was hired by Mr. Anthes to meet the steamer Fairhaven each night to deliver and receive the mail at the Langley dock which was located in 1900 at the foot of Anthes Avenue. The steamer would arrive anywhere from midnight to two or three a.m., so I slept in the warehouse at the end of the dock. My pay was S10 a month.

“In the summer of 1906 Arnold Bosshard and I worked in Everett. Our sweethearts lived in Langley, (Alice Howard and my sister, Alice). The only way we could get home on Saturday nights was to hire a rowboat for $2 for the week-end. We had two sets of oars and a small sail. We left Everett at 7 p.m. Saturday night and with good luck we would arrive at Langley at 10 p.m. Our sweethearts would always be at the dock waiting for us. We generally sailed back Sunday p.m. with a fair north wind.

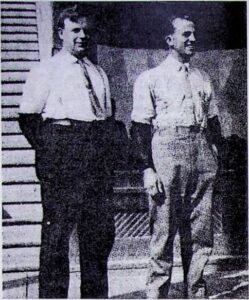

Walter Hunziker (left) stands next to his brother Bob in front of the Langley Mercantile and General Mer-chandise Store. The picture was taken in 1913.

One dark night the tide carried us on the south side of Hat Island instead of the north side which was closer. We would watch for the light at Sandy Point to guide us and by looking over our shoulders occasionally we would eventually get home. This night there was no moon and we saw what we thought was the Sandy Point light and kept rowing until the moon came up and what we thought was the Sandy Point light was a lantern on the end of a boom of logs on its way to Seattle. We discovered we were opposite Clinton. We got to Langley at 2 a.m. Our sweethearts were waiting for us. We were married that fall.

Salmon were so plentiful that I recall killing salmon with our oars as we rowed through schools of them on their way to the Snohomish River. I also recall a fish trap at Maple Cove that once had so many salmon they could not raise the net. They notified the town that we could have all we wanted for 5 cents each. I got a horse and wagon and sold a load of them at 10 cents each.”

Walter Hunziker, Sr.