It is not stretching facts too much to say that one of the reasons Maxwelton was founded was because Peter Mackie’s cow was determined to go to the University of Washington in the summer of 1905. “Bossy” wasn’t interested in education, but was after the lush green grass on the university property. Her repeated feasting thereon brought forth a hue and cry of protest from the authorities.

The roving bovine belonged to Peter Howard Mackie and his wife Ada Hawley Mackie, who were living in the Ravenna district near what was then the city limits of Seattle. Peter was working on construction of some of the fraternity and sorority houses on Greek row. This trouble with the cow was not the first problem Peter and Ada had encountered with cattle.

Shortly after their marriage in the 1890’s’ in Oceola, Nebraska, where the entire Mackie clan had settled after coming from Scotland via Mayford, Canada, Peter and Ada had taken up a homestead in Wyoming and had fenced their property. Cattlemen, however, were determined to keep everything in open range land. The Mackie fences were tom down and their crops trampled by herds of grazing cattle. Discouraged with homesteading, they next established a home in Pasadena, California, without notable financial success. When word reached them of fortunes to be made in gold mining in Alaska, Peter sent his wife and children back to the Mackie family headquarters in Oceola, Nebraska, and he headed north.

When Peter reached Seattle, however, he discovered that the city was in the process of rebuilding after its disastrous fire. He decided that a pay check in the hand was better than gold in a dream, so he started work as a carpenter, bringing his family from Oceola to the Ravenna house. Ada was a firm believer that no well-regulated home filled with children should be without fresh milk and eggs, so the cow and a flock of chickens had been added to their possessions.

The chickens showed little interest in the university’s green grass and none whatever in its educational opportunities. They remained on home turf, but Bossy was another matter; it finally became plain that either the Mackies or the cow would have to go. There was no question of what to do. For some time, the Mackies had been looking for acreage where their children and their livestock could have enough space to enjoy life.

While Peter and Ada had been adventuring in Wyoming, California, and Seattle, Peter’s brother Theodore had purchased land and built a large house on the brow of the hill above Admiralty Inlet about two miles up the beach north of Scatchet Head. When Theodore learned that Peter and Ada were seeking acreage, he urged them to join him. Together with their other two brothers, Herbert and David, who arrived from Oceola, they purchased the 900 acres which had been homesteaded in 1863 by Luther Moore and later sold to Mike and Mary Lyons in 1870.

Mackie house & barn in the background. Black and White photo hand tinted.

Peter was convinced that Theodore had found the ideal spot to establish a home and raise a family. The view was breathtaking with the rugged Olympics in the distance and ocean boat traffic through Puget Sound in the foreground. Best of all, from the beach inland were thousands of acres of undeveloped forest land interspersed with the farms of a handful of settlers. When the four Mackie brothers closed the deal on the land, David, the poetic brother, christened their new kingdom “Maxwelton” in honor of his favorite Scottish song “Maxwelton’s braes are bonnie.” Peter obtained a beach cottage for Ada and the children until a permanent house could be built.

On a July afternoon in 1905, Ada Mackie stood on Maxwelton’s beach guarding a crate of cackling chickens while she watched her cow being shoved overboard from the deck of the stern-wheeler Skagit Queen anchored offshore. Her husband was struggling to load their worldly belongings including a day-old calf onto a barge to be floated ashore on the incoming tide. Bossy thrashed about in the cold salty water, bellowing and irate at the indignity she was suffering, but eventually she paddled her way to shore where the older Mackie children took her in tow.

Finally, everything had been transferred from the boat to the beach and it was decided that the family would stay at Theodore’s house on top of the bluff until they could get settled in the beach cottage. The road up the hill was steep and Ada was nearing her time to give birth to another child; so, Peter hitched the team onto a sled and started to give Ada a ride up the hill. The sled started with a jerk and Ada fell off. Peter managed to get her back onto the sled and safely up the hill. Three months later, Alden was bom and he carried the nickname “Skid” all through his life. Whether the pet name was due to his mother’s skid from the sled is not known.

All told, Peter and Ada became the parents of twelve children including the twins Emily and Julia, and sons Wallace, Hiram, and Joseph, who came with them to Maxwelton, and finally Alden, James, Florence, Jeanette, Vincent, Clayton, and Donald, who were born on South Whidbey.

There were few roads across the interior when the Mackies settled in Maxwelton, so the four brothers bought a gasoline launch, the Sydney, and went to Everett to buy food in wholesale lots—50- pound bags of sugar, three sacks of flour, and cases of other goods. Clothing was ordered by mail from the Sears or Montgomery Ward catalog. Each year just before Easter, the girls would get new black patent-leather shoes with gabardine tops. To determine the proper size, the girls would stand on a piece of paper and have their feet traced, and the tracings would be sent along with the order.

Shortly after their arrival at Maxwelton, the Mackie brothers bought a big breaking plow and a span of four horses. With these, they plowed 300 acres of land and planted oats, an assortment of fruit trees, and a large garden. They added chickens and cows to their farming operations. With the proceeds from the garden, orchard, and livestock —plus fresh fish from the bay and venison and wild fowl for the taking—the large family was well fed, needing little from a grocery store.

Joseph Mackie, who was four years old when his family moved to Maxwelton, described in a 1982 interview how food was obtained when he was growing up. “Relatives went deer hunting every fall, or whenever they wanted meat; with no hunting season, they didn’t have to get a license. At first there weren’t any rabbits, probably because of the wetness of marsh. Later, rabbits were brought over as pets—and then went wild. Old J. D. Montgomery used to go bear hunting. You had to have a dog to chase the bear up a tree. The logging camps had some meat brought in— mostly venison. They had hounds to chase the deer into the water; men would then rope and drag them to shore. There were ducks and geese on the marsh in fall; when the grain had fallen from the stalks, it would be black with ducks.

“San Juan Fish Company had many fish traps. One could go there and get lots of fish. There was a humpy run every four years. Once, the trap was so full of fish that they couldn’t raise the nets, so they ran a pile driver right alongside and had a great dig net fastened to a scow, brought the line up, and filled the whole scow with fish. I ran my boat right up beside the scow and filled it so full of fish that I had to keep my feet up in the air in order to row home. We also used to get fish from the Indians each year when the Snohomish and Kalalock tribes would come in many canoes for a potlatch at the old Oliver Place on Useless Bay. They were not hostile and used to chant ‘we want bread!’ So, mother would trade some of her home-made breads for fish. Also, we had a ten-acre orchard and they would trade fish for prunes. Whole families of Indians came—not just the men. They would potlatch for a week with feasting and bonfires. They would dig clams at Double Bluff.”

Joseph’s sister, Julia Mackie Brixner Cross, had some recollections of her own about the Indians. “They came in long Indian canoes from Hood Canal and we could hear them coming because they were singing in rhythm as they paddled. We girls were afraid because of stories my father had told about the war-like Indians in Nebraska, but our brothers would go down to the water to meet them, taking some kind of fruit which they would trade for big slabs of smoked salmon.”

Julia also recalls that although there was a wagon road along the edge of the marsh, there was no bridge across the creek which ran through it. Teams and wagons simply forded the creek,’ but the girls would sit down on a big rock, take off their shoes and stockings, and wade through the water. She also recalls that when it came time to pay their real estate taxes, her father would take a horse and buggy and drive the 38 miles to Coupeville, staying overnight and returning the next day.

The tide flats were the children’s playground in nice weather, and they played baseball, had parties, and went swimming. The girls also had household chores to do and Julia recalls some of these times graphically. “We girls had to feed the chickens and pigs and also do housework. I was the sweeper. Emily said that her back hurt, so she did the dishes. This tickled me pink because I hated to do the dishes. Emily loved to read and she would read all the time—even in bed by the light of the coal oil lamp. Father would see the light from the lamp shining on the apple tree outside our window and he would call out, ‘Emily, are you still reading?’ She would answer ‘Yes!’ and he would say, ‘Well, put out that light.’ After the third time, he would get really serious about it, so Emily would pull the covers clear up over the head of the bed and put the lamp under the covers. The smell was terrible. I would hang my head over the edge of the bed to get away from it.”

There was no doctor closer than Everett during the Mackie’s early days at Maxwelton, so Ada nursed her brood of twelve youngsters through chickenpox, whooping cough, and measles—as well as all the lesser ailments. It seemed that the children always got sick at the same time. She was very skillful with home-made remedies. She also served as midwife to most of the women in the area. The neighbors often turned to the Mackies in times of trouble. Joseph remembers a time when he and his brother, Jim, had to take a logger, who had cut his foot, to a doctor in Edmonds.

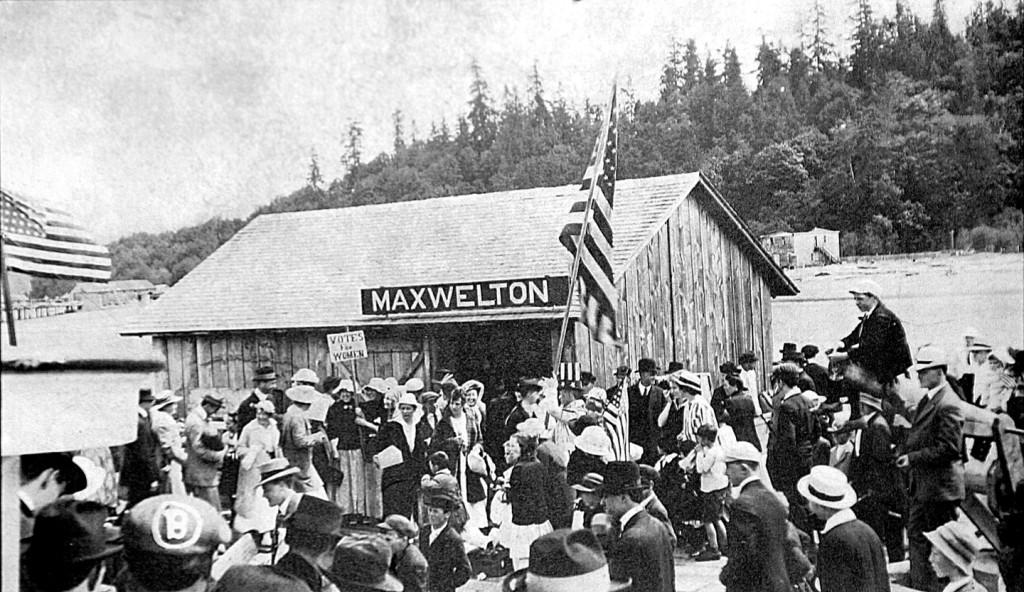

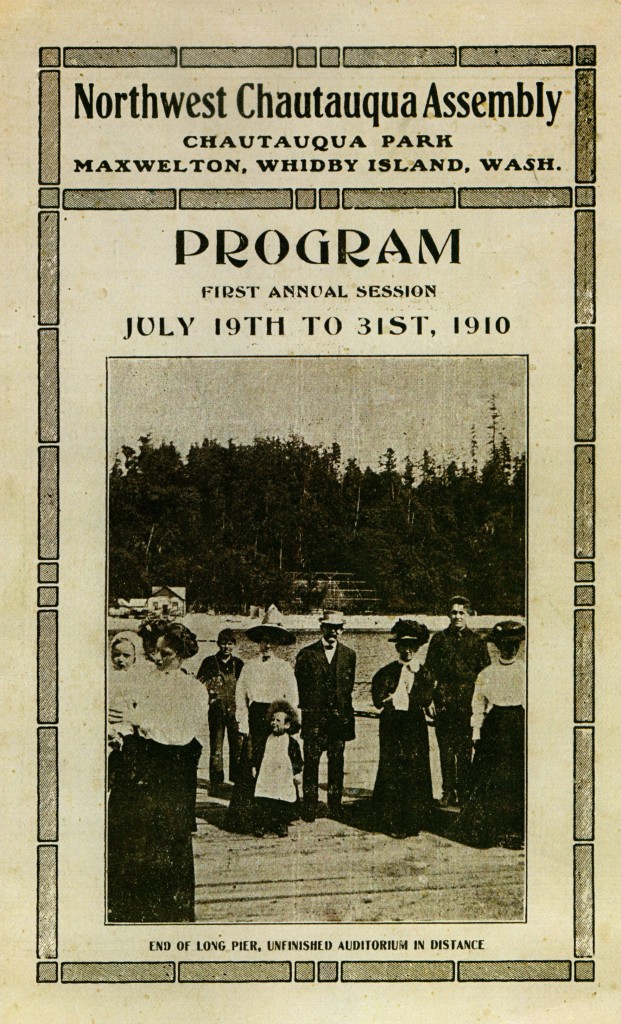

They went in their launch. On the way to ease the pain and stop the bleeding, they poured whiskey on the wound. “You drink some, too, you know,” Joseph added. Joseph also remembers several interesting facts about the Chautauqua. Mrs. Spangler was the receptionist for the Chautauqua when its regular programs started and Joseph was a page. He also sold papers and took down and put up tents. William Jennings Bryan was the speaker at one of the programs; another time, Ross Crains, a cartoonist, gave an illustrated talk. Evangelist Billy Sunday was still another speaker. There were band concerts, magicians, and plays, “some of them quite risque for that era” according to Joseph. Julia remembers that there was a dining hall where The Chautauqua Society served dinners and people would come from Everett and Seattle by steamer for the programs.

Chatauqua in Maxwelton in 1910

The Chautauqua came to an end during the big snowstorm of February, 1916 when there was four feet of snow on the ground and on the roof of the auditorium. The men in the neighborhood shoveled snow until darkness brought things to a halt. They planned to get the remaining snow off the roof the following morning but in the night the rain came and a large maple tree, loaded with wet snow, toppled over onto the auditorium roof, flattening it, bringing to an end Chautauqua performances at Maxwelton. They gradually died out elsewhere as the more urban and sophisticated Lyceum circuit replaced it.

About the same time, Joseph remembers, another storm took out the dike protecting the farm land on the marsh, permitting the salt water from the bay to rush in. It was five years before any crops could be grown on that land as a result.

About the same time, Joseph remembers, another storm took out the dike protecting the farm land on the marsh, permitting the salt water from the bay to rush in. It was five years before any crops could be grown on that land as a result.

The Mackie children attended Island School (across from where the fire station is in recent times.) Peter was one of the directors. Julia recalls that her teacher was a Miss Kittredge, “A little old- fashioned old maid, scared to death of men. She would get all jittery, completely undone if a man appeared on the scene.”

After finishing eighth grade on Whidbey, Julia went to Everett by steamer to attend high school, graduating in June 1914. The following September she started teaching in Greenbank, riding there on horseback each Sunday evening and returning home the following Friday evening for the weekend. When it rained, which was often, she would hoist an umbrella over her head, holding it firmly in one hand and the reins of the bridle in the other.

Romance entered Julia’s life in the form of Myron Brixner a few years after she started teaching. They were married and had three children—Raymond, Geraldine, and Loren—who died at the age of 17 in a boating accident. Her husband also died and Julia moved into her parents’ home.

Maxwelton had become an attraction for summer campers. They would come to the Mackie house and ask to buy provisions so Julia conceived the idea of opening a store on the beach and thus was born the Maxwelton Store which was still operating (under other owners) in 1985.

In the course of time Julia met Raymond Cross, superintendent of an apple orchard in the Lake Chelan area, and they were married. He died several years ago but Julia was still living in the home she has occupied for the past 73 years in Maxwelton in 1985.

See also: Maxwelton

See also: Julia Mackie Brixner