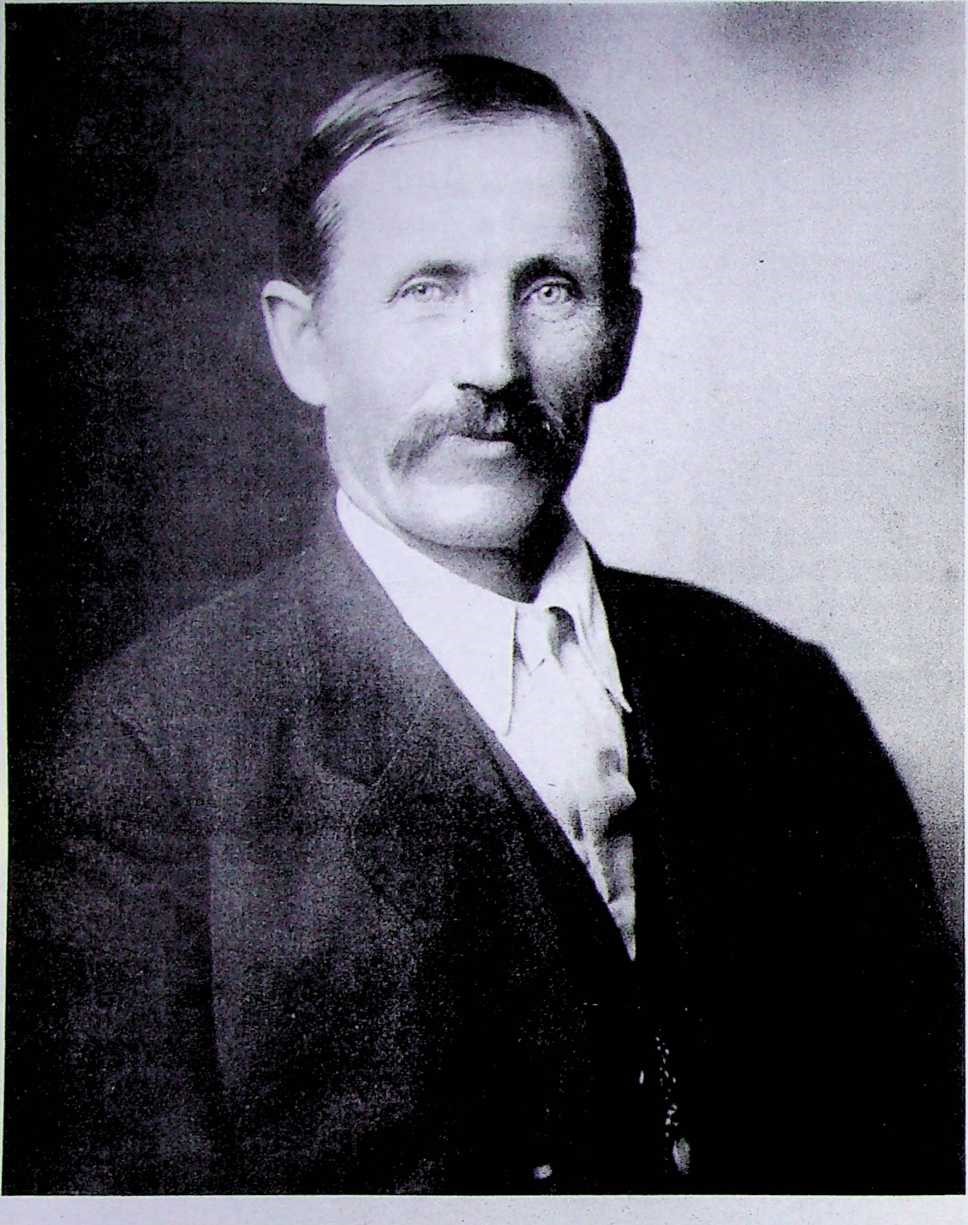

If Herman Kyllonen had been able to gaze into a crystal ball and see his future back in the 1880s when he left his native Finland to seek his fortune in America he would have been pleased.

He would have been pleased to foresee that in 1889 he would homestead 160 acres in the southern part of a beautiful island called Whidbey and that his home there would become the social center for a hard-working but fun-loving group of fellow Finlanders. He would have been pleased to know that three years later, 1892, he would meet a charming lady from Finland, newly arrived in Seattle. They would marry and make their home in the log house he had built on his island domain. He would have been pleased if he could have foreseen that he would become the father of 12 children who would be healthy, happy, and well liked in the community.

One thing he could not have foreseen was that he would become famous (notorious?) as the man who dug a 100-foot-long, five-foot wide, eight-foot high tunnel through a hill just for the fun of diverting a spring-fed stream of water into a small lake in his yard. His youngest son, Theodore Kyllonen, who lives in Edmonds as this is written, recalls the incident with humor.

“I guess Dad really just wanted us boys to have something to do to keep us out of mischief when he started the tunnel. We had a little lake way off at the far end of our property. He thought it would be great to have another one between the house and the barn. His intention was to divert the stream on the far side of the hill through the tunnel, form a lake, and then let the overflow return back to the original stream.

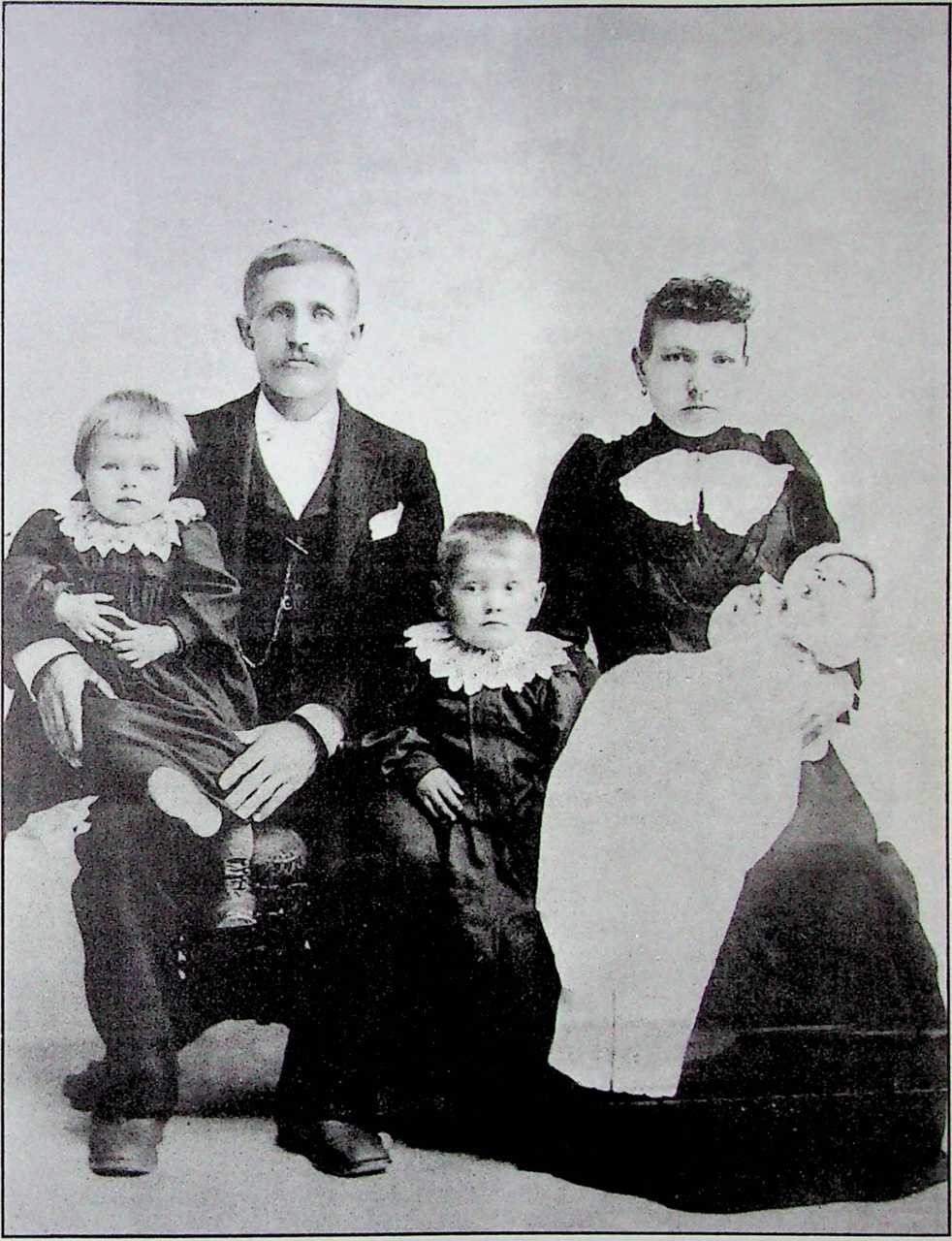

Herman and Finna Kyllonen about 1895 with their oldest son Swante, center, daughter Olga right, and

baby Lena on her mother’s lap.

“The trouble was that the soil, where he put the lake, must have been unusual because, instead of filling and sending the overflow back into the original stream, the lake would only raise to half full. Then the water would just disappear into the ground.

“It was quite a mystery. We figured it must have something to do with peat moss because further over on the property there was a patch which had caught fire somewhere along the way. It had smoldered underground for several years.

“My brothers, Harvey and Leonard, and I worked, digging the tunnel for almost a year. Our oldest brother, Swante, was grown by that time and off on his own. The tunnel became the center of attraction for all of the kids in the neighborhood who loved to play there but we were careful not to step in the little stream that ran along one side.”

The Kyllonens in 1929 from left to right: Aili, Theodore, Harvey, Amelia, Linda, Marie, Alma, Hilda, and Swante in the back.

Selma Matilla Green and Arlene Auvil Chambers are among those to remember playing in the tunnel. Clay Green remembers it clearly, and describes its construction. The sides were cedar posts which supported a solid roof.

Theodore Kyllonen recalls that his father had designed an excellent water system using the 250-foot drop from the top of the hill above their house to provide gravity powered running water for the house and bam. Another of his recollections is that of working for Wells and Wheeler farms which extended all around Miller Lake. Acres and acres of carrots and onions were grown by the firm commercially and the Kyllonen boys were among others who were employed packing the products in boxes for market.

Swante Kyllonen became famous for his skill as a tree topper, giving demonstrations of the art at the

Island County Fair and on several TV programs.

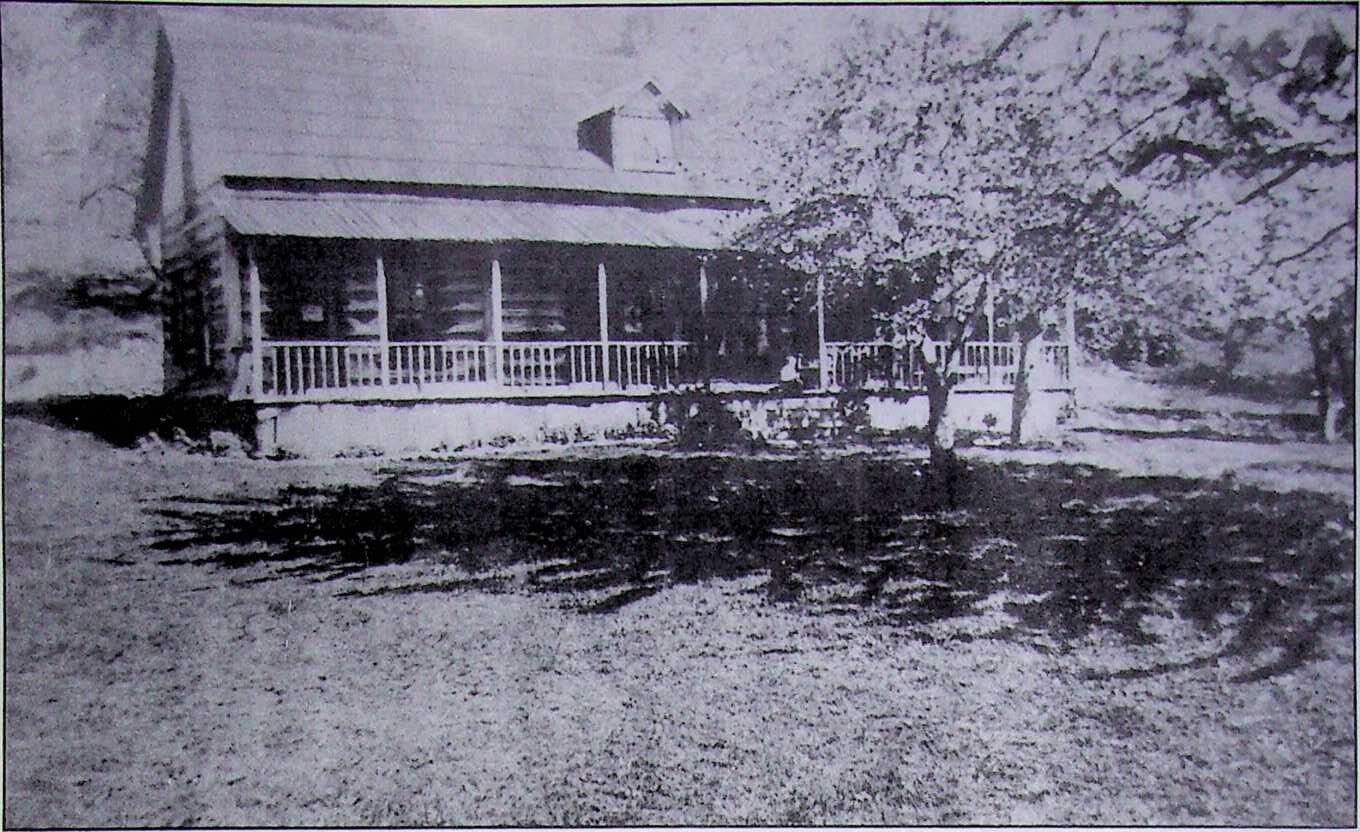

Herman Kyllonen was in the business of logging, cutting timber into cord wood for the woodburning steamers that docked at Langley, Clinton, and Glendale. Originally his 160-acre homestead was wooded. He used some of the logs from the land to build his house which he later added onto, constructing a sort of social hall with a large Finnish sauna and a floor suitable for dancing. On Wednesday and Saturday nights folks from all around the community, many of whom were Finnish, would come to enjoy the sauna and pot-luck dinner, then dance there until daylight.

After the trees had been harvested, Herman platted his property into 40-acre tracts of stump land which he sold to in-coming settlers. He retained the home plot and 30 acres for his family. Herman Kyllonen is remembered as being a stem no-nonsense type of person with a high sense of honor.

He developed a highly productive ranch and is credited with harvesting produce which he would share with his neighbors until they were able to clear their land and produce crops of their own. Arlene Auvil Chambers, whose aunt Birdie married Swante Kyllonen, recalls an incident which reveals his character. When the call went out for bids on clearing the land for the Woodland School, Kyllonens received the job. They had bid the work at $400. Unfortunately, it turned out that the dynamite alone for blasting the stumps cost over $400. The Kyllonens paid out more than they received, but they insisted on standing by their agreement and taking their loss.

As this is written, four of the eight Kyllonen daughters are living in Seattle: Alma, Hilda, Aili, and Amelia. Theodore Kyllonen joined the United States Marines, serving 28 years. He married the former Ada Marie Craw, daughter of another prominent Midvale family and they live in Edmonds as this is written.

Swante Kyllonen became famous for his skill as a tree topper, giving demonstrations of the art at the Island County Fair and on several TV programs. He married a relative of the Auvil family and the account of their courtship follows in the Auvil story. He and his wife lived on part of the original Kyllonen property for several years. They moved to Olympia when their son became seriously ill and required continuous hospital service. Swante worked as a logger near Shelton.

Much of the Kyllonen property is now owned by the Chinook Learning Center, as this is written.