The Ike and Kittie Bainter family left their mark on Langley, being remembered for their hospitality, music, and civic involvement in the early days of the city’s incorporation. Their 18-acre farm was a social center for community parties and potlucks.

In his book, The Langleyites of Whidbey Island, author William McGinnis described Kittie (Johnson) Bainter, who was evidently a hugger.

In his book, The Langleyites of Whidbey Island, author William McGinnis described Kittie (Johnson) Bainter, who was evidently a hugger. “Mrs. Ike Bainter was another of my favorite Langleyites. She was one of the real Alaskans… of average height, but broad and strong like a grizzly. Anyone wandering within range of her solid arms was brought to a halt. Struggling was useless.”

“Mrs. Ike Bainter was another of my favorite Langleyites. She was one of the real Alaskans… of average height, but broad and strong like a grizzly. Anyone wandering within range of her solid arms was brought to a halt. Struggling was useless.”He went on to describe some of the difficulty she had pronouncing English words: “It didn’t seem to matter though because there was so much motion and good natured laughing going on that you always knew what she meant.”

“I ate supper at their house quite a lot,” he wrote. “Every time you looked away she put something more on your plate.”

Neighbor Ester Anderson Moe also had fond memories of the Bainter home as recorded in Lorna Cherry’s book, Langley, The Village By The Sea.

“…I used to love to go to their house. They had a phonograph with a big horn. They had a sink! And a drain lined with zinc so you didn’t have to carry out dishwater. They had an organ, too.”

Cherry goes on to describe the Bainters as music lovers. The Victrola drew neighbors from all over the community to listen to the marvelous machine that played music.

“During summer evenings, folks would sit on stumps out in the yard and listen to records which were often played until midnight,” she wrote.

“During summer evenings, folks would sit on stumps out in the yard and listen to records which were often played until midnight,” she wrote.The organ provided a great deal of music as well. Although Kittie never learned how to read or write, she did learn how to play the organ. In fact, the whole family was musical.

The Bainter girls, Flora, Lucy and May, became famous in the community as a vocal trio and frequently performed at weddings, parties and funerals.

Kittie was also esteemed for her cooking, tidy housekeeping skills, sewing skills, gardening and canning. Potlucks at the Bainter home were a frequent occurrence.

Like many families who moved to Langley in its early days, they were seeking a better life. In their case, they had been advised to relocate to a milder climate for their daughter Flora’s health, as well as wanting better schools for their children.

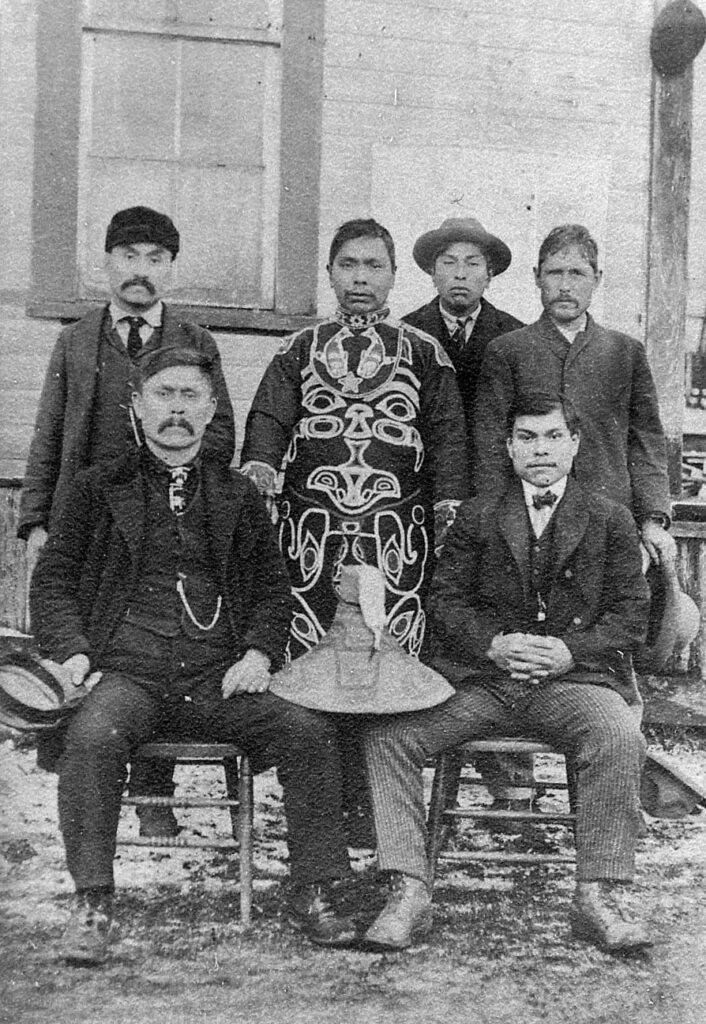

Theirs was not the only mixed-race marriage on South Whidbey, as several early white settlers had married women of the local Snohomish Tribe.

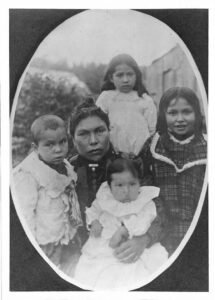

Kittie, however, was a Tlingit woman from Sitka, Alaska, born June 1 in either 1865, 1867, or 1869 according to different census records.

Kittie, however, was a Tlingit woman from Sitka, Alaska, born June 1 in either 1865, 1867, or 1869 according to different census records.Family lore has it that she was highborn in the local clan, possibly the niece of a chief. (The family is currently exploring DNA matches and records to corroborate this.)

A trip to Sitka in 1981 by Kittie’s great-granddaughter Gayle Cattron Pancerzewski, yielded valuable information when she and husband, Charlie, met a relative of Kittie’s.

Andrew Peter ‘AP’ Johnson, was a lifelong Sitka resident and Tlingit, widely known as a local historian.

He described how the Tlingit are a matrilineal society with lineages traced through the mother’s side. In addition, each Tlingit person descends from either the Eagle or Raven moiety. This distinction was important in all aspects of the culture as marriages were to only be between eagles and ravens and not eagles to eagles or ravens to ravens. Each moiety is further subdivided into clans, and each clan is subdivided into houses.

AP offered that Kittie was a Sitka Kaagwaantaan (Wolf) which is part of the Eagle moiety, and Kookhittaan (Box House Clan) that is a sub clan of the Kaagwaantaan.

AP offered that Kittie was a Sitka Kaagwaantaan (Wolf) which is part of the Eagle moiety, and Kookhittaan (Box House Clan) that is a sub clan of the Kaagwaantaan.Kittie’s paternal side has not been determined, but AP suggested that if the family found that her father had a frog for an emblem, he may have migrated from a northern location to the Sitka area. Kittie’s father would have been from the Raven moiety.

Before Coming to Langley…

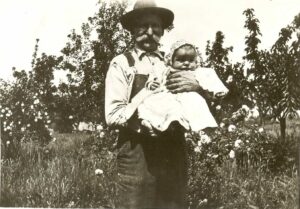

Isaac “Ike” Marian Bainter (later nicknamed ‘Handlebars’ for his long waxed mustache) was the youngest of nine children born in Blountsville, Indiana in 1859. His parents were settlers who hailed from Pennsylvania and Ohio.

Ike lost his mother at age 4 and his father at age 6. It is likely he was raised by older siblings.

At the age of 21, he set out west to the gold and silver fields in several western states including California and Oregon. In 1886 he went north to prospect in Alaska, 10 years before the gold rush. There he also tried his hand at logging, worked at a lumber mill, brokered barrels of salmon at a cannery, and was a survey agent of coal fields for investors.

Ike and partner Jim Tak were hired by Frank Watson, who represented midwest investors, to find the ground that they purchased, and stake it out.

Ike and Jim also staked their own claims but were not able to clear title before the Federal Government took the lands in a “take” similar to eminent domain so that the government could profit from the coal and not individuals, companies, or trust monopolies.

Ike met Kittie at an Army Post social hall in Sitka, where she worked as a maid. Unfortunately, he came down with either Typhoid or pneumonia and was close to death. Kittie nursed him back to health and is credited with saving his life.

According to author William McGinnis, there was a family tale that Kittie had saved Ike’s life by sledding out to get him on a snowy trail when he was sick with pneumonia. Whether this was the same illness or one at a later time is unclear.

Love grew and the two were married in Jackson, Alaska in 1887. He was 28, and she was either 22, 20 or 18.

Census records state that Kittie had seven pregnancies, but only four children survived to adulthood.

Daughter Lucy was born in 1893 on Dall Island; son Marian was born in 1895 at Sucquan, Prince of Wales Island but died seven months later; daughter Flora was born in 1897 in Sucquan; son Daniel in 1899 at Copper Mountain Harbor on Prince of Wales Island; and daughter May in 1901 in Klawock on the same island.

The family lived for several years in Howkan and then moved to Sitka in 1903. During this time Ike staked claims in coal fields and gold mines, and also placer mined for gold.

In March 1906, the Bainter family departed Sitka, planning to move to southeast Oregon, but on the advice of friends onboard, they took a passenger boat out of Seattle to Langley.

They purchased the Felton home and farm on 10.5 acres in the Northview area of Langley in 1906 for $2,000, and a year later an additional 7.5 acres next to the farm for $250.

The Bainter farm had just about “everything,” and was planted with raspberries, loganberries, strawberries, cherries, plums, apples, rhubarb, cabbage, peas and potatoes. They also had chickens, cows and pigs.

The Bainter farm had just about “everything,” and was planted with raspberries, loganberries, strawberries, cherries, plums, apples, rhubarb, cabbage, peas and potatoes. They also had chickens, cows and pigs.The fruit as well as eggs, cream and butter were sold locally and in Everett.

The Bainters were members of the North Pacific Cooperative Berry Growers and were issued stock in March of 1920.

Ike kept ledgers of the farm accounts for labor, yield, and sales, recording whopping berry yields. For example, in 1924, more than 9,000 pounds of loganberries were picked and sold!

In regards to his apple crop, there was not much of a market for apples and most of them were left to rot on the ground.

Author William McGinnis gave this account of a solution that Ike and three friends (McGuinnis’s father, Bill; Jim Tak; and Dr. A. J. Craig) came up with: making hard cider.

Using Ike’s cider press they filled a 52-gallon barrel adding a pound of unsalted butter, two pounds of flaxseed for clarity, and four pounds of sugar.

They hid the barrel in Ike’s shed, turning it each week and tasting the progress of the brew.

Unfortunately the secret got out and Hugh McLeod (a lawyer and Justice of the Peace) and friend Mike Dudley started slipping into the shed and sampling the cider whenever Ike was away, drawing off a jug or two at a time.

Ike just thought that the fermenting process must be making the barrel lighter.

As Christmas approached, Ike and his friends met one night to fill their jugs for the holidays, but surprised Hugh and Mike who were filling their own jugs.

“Well, so now I know why the barrel’s light!” Ike exclaimed.

“You sneaky bums been stealin’ our hard cider, eh?” said Jim Tak.

Doc and Bill were laughing, but moved on the barrel. After filling two jugs, all that came out was air.

“Hey, Hughie and Mike, give me those jugs,” said Doc. “Here, grab those mugs – we may as well have a drink.”

According to McGinnis, they filled all their mugs and kept them full.

“Merry Christmas!” said Ike and held up his mug. Such was the camaraderie and high-jinks of early Langley.

Civic Involvement…

Ike helped establish the Masonic Lodge in Langley and helped build Langley’s Methodist Church, for which his minister brother-in-law from Indiana, gave the dedication sermon in 1909.

Ike helped establish the Masonic Lodge in Langley and helped build Langley’s Methodist Church, for which his minister brother-in-law from Indiana, gave the dedication sermon in 1909.Ike was elected to serve on the first Town Council after Langley was incorporated in 1913.

He received the most votes of any candidate and was appointed to work on several committees: Finance and Licenses; Books, Stationary and City Records; and Health and Sanitation along with Dr. Craig as Health Officer.

The Bainter family enjoyed grandson, Francis ‘Catt’ Cattron, son of Lucy and Roy Cattron. ‘Catt’ spent a lot of time at his grandparents’ farm after his parents divorced.

In 1925, Isaac received a diagnosis of extension paresis (a muscle wasting disease) which confined him to his home until he died in 1937. Kittie and daughter Flora cared for him throughout his illness.

After a bad fall in 1941, Kittie developed pneumonia and died.

Daughter May married local meat market owner Bob Frear and helped him run his popular meat market in Langley. Frear’s meat scale has been a fixture for decades and still sits on Langley’s First Street sidewalk at the site of his former market.

Son Daniel Bainter became sheriff of Langley and remained a bachelor.

Three great-granddaughters (Gayle Cattron Pancerzewski, Carol Cattron Wade, and Sharon Cattron Edwards), and two g-g-granddaughters and three g-g-grandsons still live in the area.

Thanks to Gayle Cattron Pancerzewski and her daughter Cindy for their extensive and continuing research.