During the thirty years between the arrival of Robert Bailey in 1850 and the beginning of the decade of the eighties, not more than a dozen families had established permanent residence on South Whidbey. There were several active logging operations, with small numbers of itinerant workers, but the nearest thing to an organized town was the Clinton general store, dock and post office operated by the Hinmans on the eastern shore at Columbia Beach.

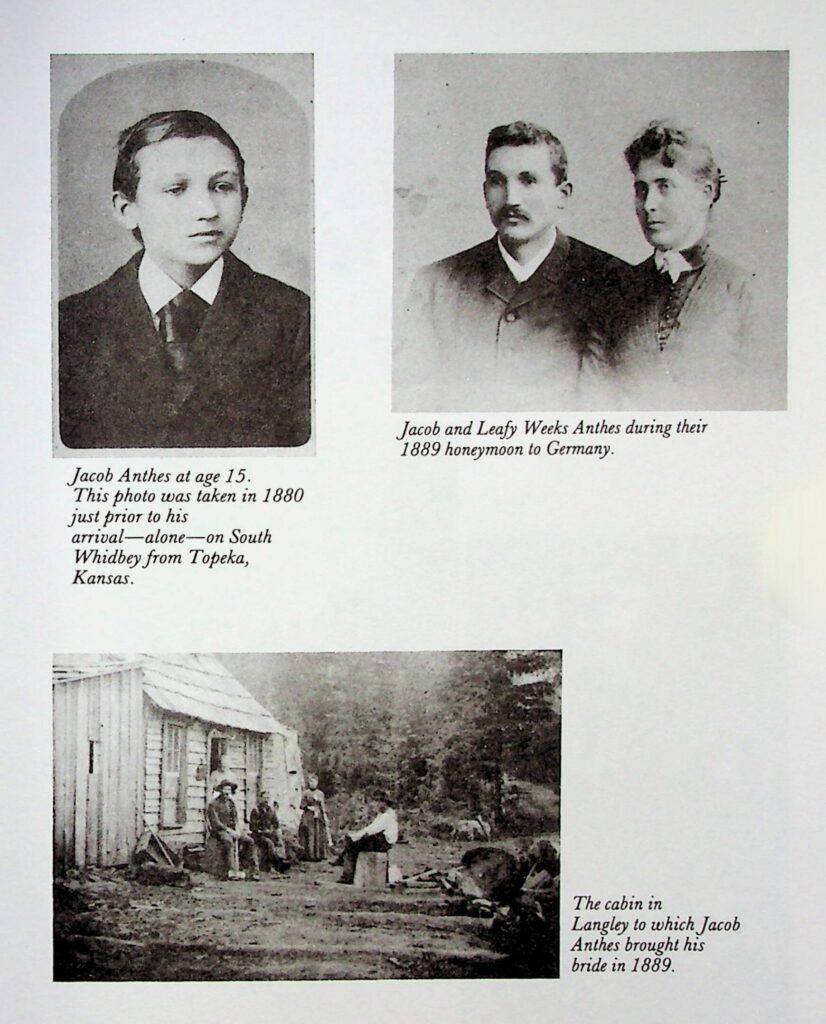

Jacob Anthes, the man who was to establish the first — and up to 1983, the only — incorporated city on South Whidbey, arrived on its shores in 1880 at the tender age of fifteen years. His story, told in his own words, follows.

Ijn the fall of 1880, in stopping at what was then the old Occidental Hotel in Seattle, I met the head waiter of the dining room. He was looking for someone to hold down a homestead on Whidby Island. This was a common practice in early days. The man’s name, as I remember, was Pat Quinn. After agreeing on terms and it promising new experiences for me, I agreed to take the job. A logger by the name of Christopher Anderson who was running a logging camp for Stetson and Post of Seattle in Useless Bay was also stopping at the same place. This land in question being about three miles from his camp, he was to point it out to me.

We left Seattle that evening at 9 o’clock on the steamer City of Quincy for Mukilteo and arrived there at midnight. Accompanying us was a man by the name of Bennett who was looking for a marsh on the island which a Dr. Van Zand had purchased for a cattle ranch. We stopped at a place run as a hotel by Jacob Fowler intending to leave early in the morning for the island. However, we had to remain in Mukilteo for several days owing to a heavy southeast wind blowing which appeared to make it unsafe to cruise around Skagit Head into Useless Bay.

After the skiff deposited us on the island, we stopped at the old Mike Lyons’ place where Maxwelton is located today. We followed what Mr. Anderson called a trail, covered with logs and brush, which showed that there had been very little travel over it. In about an hour we arrived at what he called the farm. A shack about ten by twelve feet, covered by trees and ferns, was to be my home. I fail to see to this day what possessed that man Quinn in filing on a place in such a wilderness. This was one of the first homesteads filed upon on the south end of Whidby.

I was left alone and commenced to investigate. I found that the roof leaked like a sieve and it was almost like being in the rain. I found some cedar shakes which I used to cover the part of the roof under which there was a bunk with a wet mattress on which I was to sleep. I spread my blankets and prepared to make the best of it. I started a fire in a box stove and soon warmed up the place. In looking for edibles I found some beans, mildewed bacon, half rotten spuds, and nearly two barrels of salted salmon, so I felt that I would not starve. I found a lamp, but there was no oil anywhere. It was getting dark, and having nothing else to do, I went to bed wondering what tomorrow would bring.

I had been told that there would be plenty of game of all kinds and I would not suffer for want of something to eat.

Before leaving Seattle I purchased a Sharps rifle 45-70 and felt proud in its possession. It was largely in the anticipation of excitement that I accepted the job in the first place. In passing a slough on the trip to the place I noticed the water was alive with salmon as far as the eye could reach which I would not have believed had I been told of it without seeing it for myself, and the saltwater marsh seemed alive with geese and ducks, hardly paying any attention or showing any fear. I did not sleep well owing to the wind howling in the trees and I was glad when it showed a dim light through the opening intended for a window indicating that daylight was near.

I heard a funny noise near the cabin and venturing to the opening I spied a large deer within twenty feet of me on the trail. He saw me but did not move. I got my rifle and was all excitement. I fired three times without touching him with him standing there looking at me. He turned and passed out of view taking his time in so doing. Judging from the fir needles I saw drop, I fired at least ten feet over his head.

After a breakfast of potatoes and bacon and black coffee, I started for a stroll. It was raining but I did not mind, having an oilskin coat which kept me quite dry above, but from the hips down I was wet all the time as the brush was thick and wet. Some distance from the cabin I heard the barking of dogs and a sort of bleating sound. I ventured carefully toward the noise and saw two vicious looking hounds on top of a deer. When they saw me they showed their teeth like a pair of wolves. They frightened me and I took aim at the larger one which was not more than thirty feet from me. He gave a yell, made one big jump, and was still. The other turned around and ran off and I never saw him again. I found the deer had been hamstrung by the dogs and a good part of its hind legs eaten away while it was still alive. I killed the deer and had plenty of fresh meat for several days.

I did not do any slashing or clearing as it continued to rain but found plenty of time to look around — to hunt and investigate. Game such as deer, pheasants, ducks and geese was plentiful, and I could spear salmon in the slough with a sharp stick. So I lived on fresh meat and fish almost entirely. For a young fellow of my disposition this indeed seemed paradise. I cleared out the trail to the beach about three-quarters of a mile between showers and was making a little headway in opening a clearing around the house. I spent nearly three weeks in eating, sleeping, hunting and doing a little work on the ranch without seeing anyone.

One day while I was on the beach I saw a skiff making for shore with two men and a woman in the boat. On landing they inquired regarding the very place where I was living. One of the men handed me a letter from my employer requesting me to give possession of the place to the bearer. Mr. Quinn had relinquished his claim to his new party. They were more surprised when they saw the ranch than I had been. They brought with them some bedding and a few groceries which the owner of the boat and I helped them carry to the house. After a good deal of whispering they concluded to make the best of it and stay. The man told me that they were on their wedding trip, but I always felt they were some runaway couple who did not wish to be found for a while. What finally became of them I do not know, but this place changed hands a number of times until John Parsons stuck to it and made it one of the best ranches on the south end of the island.

I packed my few belongings and left them in a corner of the house and returned with the boatman to Mukilteo on my trip to Seattle. I found Mr. Quinn at his old place and he seemed well satisfied with what I had done. He paid me at the rate of $1.50 a day and I felt well satisfied. I met Mr. Bennett, my first fellow passenger on my trip to the island, who was going to open a trail to Sandy Point for the purpose of driving cattle to Mr. Van Zand’s farm, some 300 acres in extent later known as the Miller Ranch and now owned by Mr. Feek.

He assured me of a job and we returned together that night to the island. His camp was about two miles from the beach and there were four of us to work on this trail. We completed it in about a month. One hundred head of stock was landed at Sandy Point and driven to the place. It commenced to rain and rained for a week and the marsh became a lake two and three feet deep. The cattle found nothing to eat, and with the exception of a few head which were sold, they all starved to death or died of footrot.

In my wanderings I met all the settlers living on the south end of the island as far as Holmes Harbor, covering a distance of fifty miles: N. E. Porter (directly opposite the head of Holmes Harbor on the outer passage), Mr. Johnson (Double Bluff), George Finn, F. George, G. Johnson, Thomas Johns, Edward Oliver, Mike Lyons (where Maxwelton now stands), Robert Bailey (Bailey’s Bay), John G. Phinney, and Joseph F. Brown of Brown’s Point, now named Sandy Point.

Beyond that for twenty miles clear to Holmes Harbor, there were no settlers. No one lived in the interior of the island which comprised one hundred sections of government land subject to entry. In addition to settlers, there were four logging camps operating during spring and summer: Stetson-Post camp in Useless Bay, run by Chris Anderson; L. McLean camp at what is now Saratoga; Eaton-Forrester camp one mile west of Saratoga; Billie Fryer camp near head of Holmes Harbor.

Mr. Joseph Brown, who had settled at Sandy Point took an interest in me and advised me to purchase land since I was too young to file a homestead. In 1881 I purchased one hundred twenty acres of land from John G. Phinney for one hundred dollars. This land is one-half mile west of Langley and was later purchased by Miss Eliza Strawbridge. Three young fellows I picked up in Seattle helped me build a log cabin on this land and we commenced cutting cord wood to supply steamers plying Saratoga Passage. We did not make any money, but we had a good time living on game, clams and fish, and this life seemed ideal to me at the time. We cleared a few acres of land on which we grew all the vegetables we could use and sold several tons of spuds to the camps the following season.

This life gave me every opportunity to explore the island and nearly every section, corner and rock was known to me. I found that nearly all the ridges and high hills on this part of the island run in such a way that the place where Langley now stands could be reached without crossing any of them from any part of South Whidby.

In 1886, when I was twenty-one, I filed a homestead on 160 acres adjoining the present town of Langley and followed in quick succession with a pre-emption and timber claim, earning sufficient money in logging operations to pay for all of them and in due time received my patents for them.

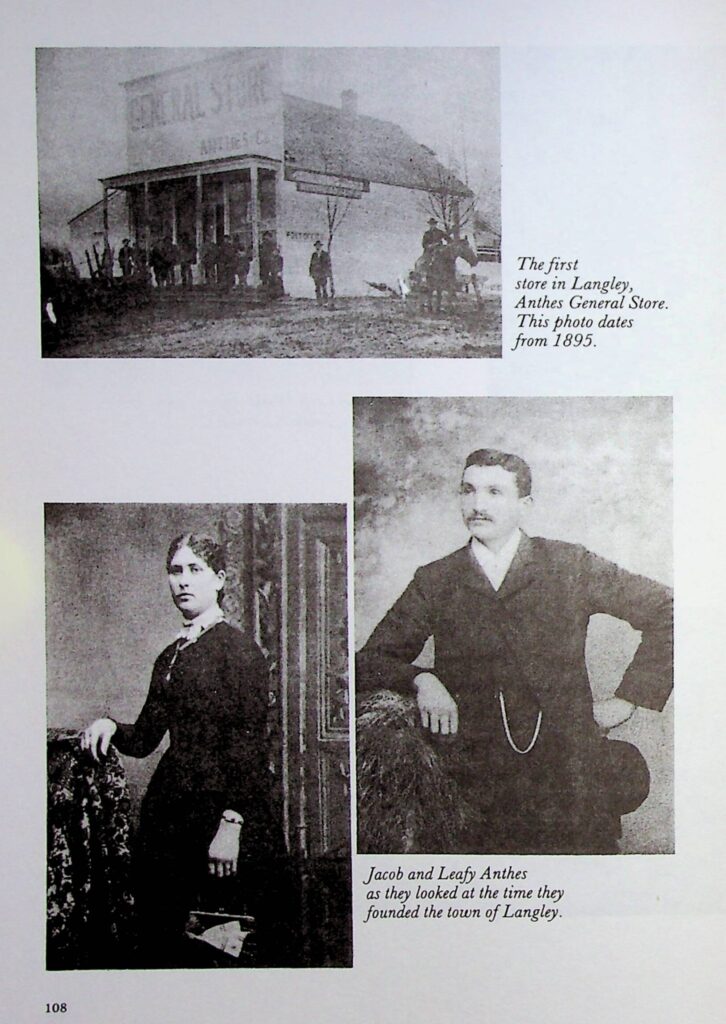

In 1889, during the building of the Great Northern Railway to the Coast, the laying out of townsites became a mania. Not being able to finance such a project myself, I succeeded in the spring of 1890 in interesting Judge J. W. Langley of Seattle in forming the Langley Land and Improvement Company. The incorporators were J. W. Langley, C. W. Sheafe, James Satterlee, A. P. Kirk, and myself, with Howard B. Slauson as Secretary. We had control of about 700 acres facing Saratoga Passage for one mile. A townsite was surveyed and platted and named for Judge Langley. A dock, costing $5,000, was built, a hotel erected, and several small cottages. I built the first residence which my family occupied for eighteen years. The vacant lands around Langley were occupied between 1888 and 1892. It became essential that a store be erected which was done in 1891, and a post office was established the same year with J. Anthes as postmaster.

At this time there were four regular steamers on the run to Whatcom, now called Bellingham. All traffic was by steam boat, there not being any railroad or other means of transportation or communication north of Seattle. There were a number of tramp steamers that plied between Seattle and the LaConnor flats during the fall and winter months carrying freight and farm produce. All of these steamers were wood burners and the call for cord wood was immense. In the years 1891 to 1893 our wood sales averaged fully 35 cords a day. In order to fill the demand, seven teams of horses and twenty-five wood choppers were required.

Langley had become a lively place. Several families moved in and we had about fifteen children of school age. A log schoolhouse was built and we procured the services of a teacher and paid him $2.50 for each pupil, assessing those fortunate in having children. The store acted as a clearing house to fulfill this agreement. The salary was not big nor were the results in learning, but the youngsters were kept off the streets and out of mischief.

We built trails and roads to the interior of the island to permit settlers to come to town and give them the advantage of trading at the store. We soon could go to Clinton or Useless Bay on horseback. Eventually the roads were widened to permit wagons to pass over them. The first county road, however, was not built until the year 1902, leading to Coupeville, the county seat. The community was prosperous in spite of the fact that the county never saw fit to assist in any way nor to spend a cent toward the upkeep of the school or roads before the year 1893 and even then it was a fight to have the authorities at Coupeville realize that there was some consideration due us, which was grudgingly conceded at last. The southern part of Whidby Island was considered not of sufficient value to warrant the expenditure of public money.

In the spring of 1894, the Langley dock went out in a storm, but it was rebuilt. Hard times, however, hit the town. Nearly all the ranchers had to leave their homesteads, there being no work of any kind and no sale of anything that they could raise. The Great Northern Railway to Bellingham carried all the traffic and there was nothing left for the steamers. One by one they withdrew from the run, and in the fall of that year there was not a steamer on the run to Bellingham or to Coupeville or LaConnor. For several years we few who held the fort received our mail twice a week by launch from Mukilteo or Tulalip.

In the year 1898 things began to look better. Several steamers made their appearance on the Bellingham-LaConnor run. The Alaska gold rush put new life and hope into everybody. Great improvements were being made in Seattle. The Great Northern built their dock at Smith Cove, and much of the material such as brush for riprapping and piling came from Langley and vicinity. About one hundred men were employed furnishing this material.

A school district was organized in 1898 and a schoolhouse built. A road district was established in 1899 and the roads were improved in the following years. A Woodman Camp was organized in 1901 and the Yeomen followed the succeeding year. A new dock was built in 1902 about a half mile east of the old one. A bank was founded by J. Langley, a nephew of one of the original incorporators of the town. A Masonic lodge was instituted about the year 1909. A new library was built. The Friends built a church in 1902, and a Methodist church was built by popular subscription in 1908. The lands around Langley were being planted into orchards as soon as cleared. Beautiful shade trees were planted along the streets which have become the pride of the little town.

The granddaughter of Jacob Anthes, Helene G. Ryan of Seattle, has written an interesting biographical sketch of her grandfather and his wife, Leafy Adelia Weeks, especially for this book, based on her personal recollections and on family documents in her possession. She has titled it, A Boy In Paradise.

Jacob Anthes was born at Gross Gerau, Germany in 1865. He was full of good humour as a lad and liked to play jokes on his friend, Adam Voelker, who later followed him to Washington and settled at Langley. The two were called Mutt and Jeff, Jacob being the one with the long legs. (Adam was short, bowlegged, and cross-eyed.) If they were caught in someone’s apple orchard, it was Jacob who made a successful retreat.

Because Jacob was smart, he attended Hochschule at government expense. He learned to recite the American constitution and Gettysberg address in English. Love of religious and political liberty became the theme of his life, and the novels of James Fenimore Cooper stirred him to the core.

At age fourteen, German boys were required to register for military service. Jacob and his friend, George Miller, decided to emigrate to America. During the five years after their departure, over a million Germans came to the United States to escape militarism and overpopulation in their fatherland.

Jacob and George were prepared to fight Indians the moment they disembarked at New York. After visiting relatives and friends in New Jersey, they traveled on to Topeka, Kansas. Some miles out of Topeka, the conductor of the train played a joke on them by letting them out on the prairie where they supposedly would find Indians.

Jacob looks like a schoolboy in the picture taken of him in Topeka, quite a contrast to the imposing man of later photographs with the elegant mustache, sun-bronzed face, and twinkly eyes. He worked for a time in stockyards alongside men who cupped their hands to drink blood from the butchered animals. He was sickened by this work and soon left for San Francisco, leaving George behind. He traveled on the first transcontinental railroad. News of the Northwest must have spurred him on to Tacoma, at that time the end of the line, and according to family legend, he walked from there to Seattle.

Seattle’s population was 3,500 when Jacob arrived in 1880. The head waiter at the old Occidental Hotel offered him a job holding down one of the first homesteads filed for the southern end of Whidbey Island for which service he was to receive $1.50 per day. It took him three hours to get to Mukilteo on the City of Quincy, and three days of waiting out a storm before he was able to make it to the island.

After he found the shack which was to be his home, a large deer approached him with curiosity and took her time before ambling back into the woods. Soon he was living on fresh meat, fish, and clams almost entirely, and “for a young fellow of my disposition, this indeed seemed paradise.”

Being too young to file a homestead, Jacob purchased 120 acres for $100 one-half mile west of the present town of Langley. He began cutting cord wood for the steamers plying Saratoga Passage, and in his spare time explored the island. He discovered that “nearly all the ridges and high hills on this part of the island run in such a way that the place where Langley now stands could be reached without crossing any of them.” In 1886, when he was 21, he filed his homestead claim on land adjoining the present townsite.

He had dreamed of adventure and was not disappointed. Once a bear chased him up a tree, and he carried the scars to prove it. He found an eagle, thought to be over a hundred years old, which had a wing span of eight feet and claws as big as a man’s hand. During the period when Orientals were being smuggled in to work on the railroads, he found a barrel on the beach with a dead Chinese in it.

In 1887 Jacob met Leafy Adelia Weeks in Seattle. Her parents were born in England and her father had arrived in America in 1856 after an eight weeks trip by sailboat. He started out as a farm laborer and ended up as a rich farmer with 1200 acres of the most fertile land in Illinois. When his wife died he was left with eight children, all under the age of ten. As a child of eight, Leafy stood on a chair to knead the dough she made into bread. Her father remarried a widow with six children and the combined families were known as the Weeks’ Army.

Leafy was twenty years old before she earned her freedom to leave home. She came to Seattle to stay with Mrs. Rachel Jones Phillips Fuller who had adopted Leafy’s baby brother when his mother died. She worked in a cracker factory while she stayed with Mrs. Fuller.

After Jacob met Leafy he divided his time between the island and Seattle. Sometimes he would row all night long through storms between the island and Seattle in order to see Leafy.

In 1887 he started a tobacco business in Seattle and at the time of the Seattle fire, June 6, 1889, he loaded his wares into a cart but someone ran off with it and he never saw the cart or merchandise again. At that time Seattle had grown to a population of 38,000.

Jacob and Leafy were married on September 4, 1889, three months after the Seattle fire and for their honeymoon they visited Jacob’s relatives in Gross Gerau, Germany. They returned to South Whidbey and settled down to housekeeping in Jacob’s cabin. Conditions at that time were so primitive that Leafy baked her bread in a Dutch oven outside in a clearing so surrounded by forest that only a small square of sky could be seen overhead. Soon the town of Langley was established and the Anthes family resided there for eighteen years. They became the parents of four children, Mabel, Cora, Howard, and Samuel.