He set fire to the woods near Clinton when he was a boy. He chased communist bandits who were bent on bank robbery in China when he was a young man. While other kids ran and hid, he played with the Indian boys who camped with their families on Columbia Beach where Deer Lake Creek empties into Saratoga Passage. He was enterprising; he would dig clams on the beach and then row the two and a half hour boat trip across to Everett to sell them for $2.50 a bag.

He was born in Clinton and educated in Deer Lake schools. Eventually he married a girl from Greenbank, built a home on Mutiny Bay Road, and has two sons and five grandchildren at this writing—all of whom live on South Whidbey Island. His family has been closely associated with South Whidbey Island for four generations.

His name is William Bergquist, and his story really begins in Sweden where his father Erick Bergquist was born in 1866. His mother, Margaret Hanson Bergquist, was born in 1872. Erick had studied engineering at the University of Sweden and felt that his opportunities were limited. In 1893, one year after he and Margaret were married, they struck out for the New World, arriving in the Scandinavian community of Strandquist, Minnesota. One of the Bergquist’s neighbors was the family of John and Goddard Erikson.

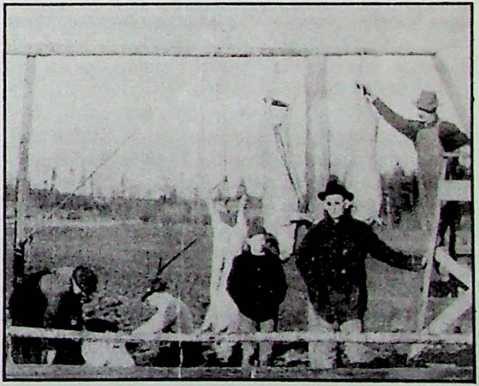

Butchering time at the Bergquist farm, 1918. From left to right: Carl, William, Robert, and Erick (father). Kneeling is Olaf Joyce, a neighbor who started a ferry system later.

During their life in Minnesota, six children blessed the Bergquist union. Times were hard, winters were severe. Word kept trickling in that there was a beautiful land with a warm climate in the far-away islands of Puget Sound, in the northwestern corner of the United States. When the Bergquist’s sixth child Edwin was a few months old, (1903), Erick packed up his wife and his children, Robert, George, Marie, Carl, Esther, and baby Edwin, and headed west.

He deposited his family in Everett briefly while he investigated the report that the nearby island of Whidbey abounded in ancient cedars which were perfect for making shingles. He made short work of acquiring 80 acres adjacent to the Orr property. With the help of his older sons, Erick cleared his property of trees, and then started a shingle bolt logging operation with his log chute located not far south of the present ferry landing. He continued this operation for several years. During that time, the Bergquists added four more children to the family—Signe in 1906, Bill in 1908, Al in 1911, and Ellen in 1914.

Shortly after his business was under way, he wrote to his former neighbors in Strandquist, Minnesota, extolling the advantages of his new home and business on South Whidbey Island. He urged them to come west and join him. They did—working for Bergquist in the shingle bolt and logging business for a considerable time. Like the Bergquist family, the Eriksons also became an important part of early Clinton history.

As a sideline to their logging business, the Bergquists also operated a fairly extensive farm producing commercial potatoes, wheat, and straw-berries. They also milked from six to ten cows and sold the cream to a main-land dairy. Between 1916 and 1918, they moved their shingle bolt and logging operation to Mukilteo where they set up a camp. They commuted back and forth in their row boat, a trip which consumed about two and a half hours when the weather was good. Teams of horses were used in the logging process, so they needed hay. There was plenty on the family farm, but not in Mukilteo, so some of the Bergquist boys built a home-made hay baler to cut and bale the hay from the farm. Then they hauled the bales to the beach where they loaded them on a dory attached to their row boat and then rowed them over to Mukilteo. From there, they hauled them with a train and wagon up to the camp.

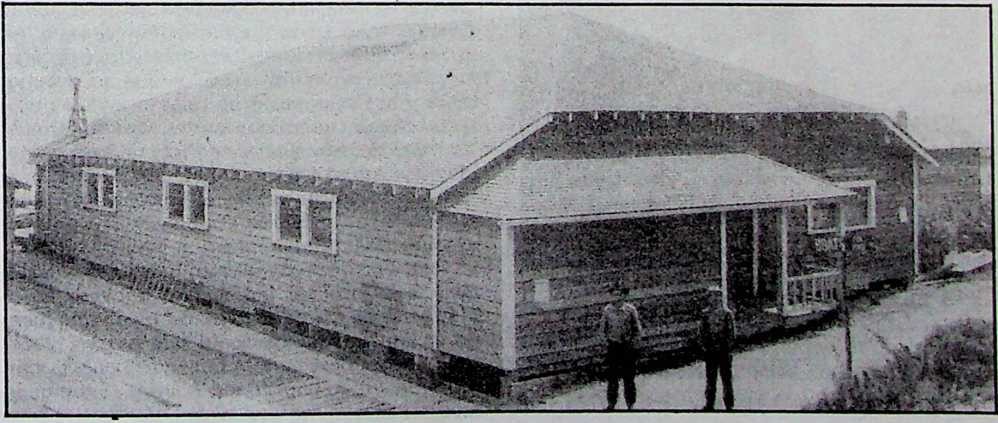

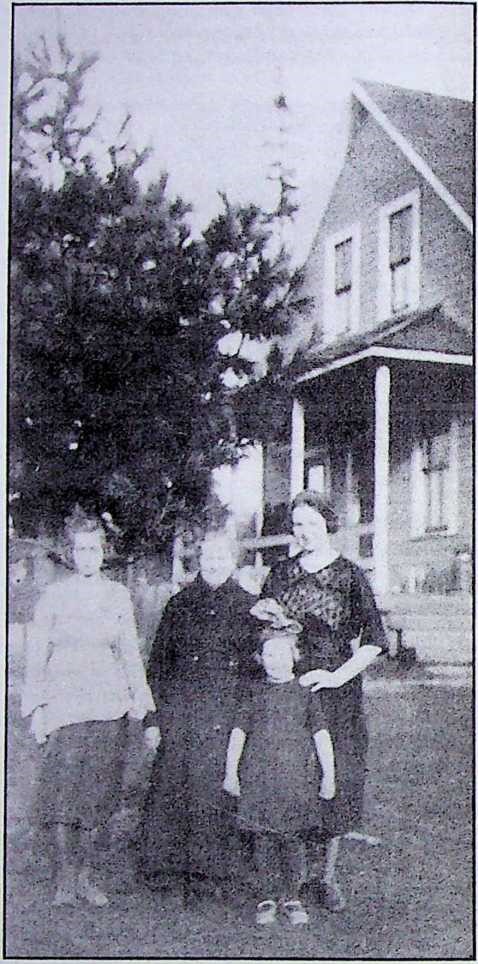

The Erick Bergquist home near Clinton, 1919. Left to right: Signe, Margaretha /mother), Ellen, and Esther. —Photo courtesy of William Bergquist.

Erick Bergquist took a leading part in Clinton’s community activities. He was one of the organizers of the Progressive Club and also became involved in politics. He was a friend of Pearl Wanamaker when she was active in Olympia and when Martin was governor. At the time, efforts were made to raise money to construct Deception Pass bridge. Erick made the suggestion, which was followed, that the state borrow ahead on the gas tax money to build the bridge.

In 1919, four of the older Bergquist boys bought the herring trap operation in Cultus Bay from a Mr. Carlson and sold bait to halibut fishermen until sometime in the 1920’s. An unfortunate accident with a pile driver caused the death of George. Robert also had been unfortunate in the matter of accidents; he was blinded while blasting stumps when a supposedly “dead” blasting charge blew up in his face.

Shortly after his business was under way, he wrote to his former neighbors in Strandquist, Minnesota, extolling the advantages of his new home and business on South Whidbey Island. He urged them to come west and join him. They did—working for Bergquist in the shingle bolt and logging business for a considerable time. Like the Bergquist family, the Eriksons also became an important part of early Clinton history.

As a sideline to their logging business, the Bergquists also operated a fairly extensive farm producing commercial potatoes, wheat, and straw-berries. They also milked from six to ten cows and sold the cream to a main-land dairy. Between 1916 and 1918, they moved their shingle bolt and logging operation to Mukilteo where they set up a camp. They commuted back and forth in their row boat, a trip which consumed about two and a half hours when the weather was good. Teams of horses were used in the logging process, so they needed hay. There was plenty on the family farm, but not in Mukilteo, so some of the Bergquist boys built a home-made hay baler to cut and bale the hay from the farm. Then they hauled the bales to the beach where they loaded them on a dory attached to their row boat and then rowed them over to Mukilteo. From there, they hauled them with attain and wagon up to the camp.

Erick Bergquist took a leading part in Clinton’s community activities. He was one of the organizers of the Progressive Club and also became involved in politics. He was a friend of Pearl Wanamaker when she was active in Olympia and when Martin was governor. At the time, efforts were made to raise money to construct Deception Pass bridge. Erick made the suggestion, which was followed, that the state borrow ahead on the gas tax money to build the bridge.

In 1919, four of the older Bergquist boys bought the herring trap operation in Cultus Bay from a Mr. Carlson and sold bait to halibut fishermen until sometime in the 1920’s. An unfortunate accident with a pile driver caused the death of George. Robert also had been unfortunate in the matter of accidents; he was blinded while blasting stumps when a supposedly “dead” blasting charge blew up in his face.

He was determined not to let his misfortune become a handicap. So he used his savings to buy property just south of the present ferry dock. With the help of his brothers Al and Bill, Robert constructed a dance pavilion. The grand opening was held in May of 1924 with live music by local talent. The pavilion proved a popular place of entertainment for about 12 years, serving part time as a roller skating rink and well as a dance hall. It was destroyed by fire in 1936. Bob, who was skilled as a carpenter in spite of his blindness, moved to Seattle where he married, earning his living remodeling houses. All but three of the Bergquist children moved from the island when they grew up.

Esther Bergquist married Carl Skarberg. They bought a part of the original Bergquist farm, but sold it in 1936 and moved to town. Ed Bergquist bought the property at Ken’s Korner now owned by Jack Bayha. Ed Bergquist and his wife Ella started a business development there including a restaurant. However, Ed and his wife separated and the development was continued later when J. D. Groom purchased it. Margaret Bergquist died in 1926; Erick died in 1950.

William Bergquist is the only member of Erick and Margaret’s family who has consistently called South Whidbey “home” up to this writing. He started school in the original Deer Lake building which was abandoned when he was in fourth grade. The new Deer Lake school was built in 1916. He finished his schooling through the eighth grade in the new school. Among his many interesting recollections of his school days, there are two he recalls with amusement, although one of them almost turned into tragedy.

While he was in sixth grade, he decided one morning on his way to school, to start a small camp-fire beside the road, not far from the Ed Swan property. It varied the day’s monotony, and besides, it was fun to watch the blaze. When it came time to continue on to school, he scuffed dirt over it, believing it was extinguished. Unfortunately some of the embers were smoldering and eventually caught into the underbrush and started a real fire. It was noticed by neighbors in time for some irate men to extinguish it before it caused any damage. Threats of a punishment—just short of hanging—were made if the culprit could be identified. Bill might have been safe except for his sister Signe (two years older than Bill) who wit¬nessed his pyrotechnical activities. She snitched to Papa. Bill recalls running right through a fence and hiding, but that didn’t save him from a whipping which he still remembers.

He redeemed himself several years later when, as a grown man, he was in charge of Civilian Conservation Corps crew working in the Deception Pass area whom he had trained in firefighting. In 1935, a fire started in the woods near the Patzwold property in Bayview and raged through the area now occupied by the Rod and Gun club. It swept on toward the school buildings in Langley. The residents in the area were unable to check the fire and sent word for help to Bill and his crew at Deception Pass. They arrived in time to run fire-stops and prevent the blaze from spreading into the settled portion of Langley.

The other incident during his Deer Lake school career was more pleasant—although almost as scary. His teacher, Miss Gertrude Matson (whose story appears elsewhere in this book) was a young lady of considerable culture. On one special occasion, she invited her class to her home for lunch in the teacher’s lodge on the shore of Deer Lake near the school. Bill remembers that his mother made him wash behind his ears, slick his hair down, and gave him strict instructions as to which forks and spoons to use, and how to place his napkin so that he wouldn’t disgrace his family on this important occasion. By the time he arrived at the luncheon, he was so nervous he could hardly eat for fear of making an etiquette faux pas.

On another occasion when he was about eight, he acquired considerable distinction by making friends and playing with a couple of Snohomish Indian boys about his age who had come from the Tulalip reservation with their families. They had camped near the beach where the Deer Lake Creek empties into Saratoga Passage. In the later part of the 1800’s, the South Whidbey Snohomish Indians had left their tribal lands and relocated on the Tulalip reservation. However, following their ancient tribal customs of harvesting and drying seasonal foods, many of them in family groups would return to the island in berry picking season, or when the salmon were running, or the clams were in season—and camp while they harvested and dried their winter store of food.

White settlers on South Whidbey Island had obtained most of their knowledge of Indians through stories of the wild west scalpings. They would bolt their doors and hide their children when Indians were known to be in the area. They had no way of knowing that South Whidbey Snohomish Indians had a reputation for non-violence and friendliness. Bill Bergquist, always somewhat of a daredevil, decided to find out it for himself. He ended up enjoying the hospitality of the Indian camp and friendship with children his age.

In the fall of 1927 Bill joined the Navy and served as a fireman on both coal and oil-burning Naval craft in the China seas and around the Philippines. The communist movement was just getting underway and the country was rife with bandits. Word came to the boat where Bill was stationed that a bank containing considerable United States holdings was to be robbed on a certain date. Sailors were sent ashore and involved in quite a skirmish before the bandits were routed.

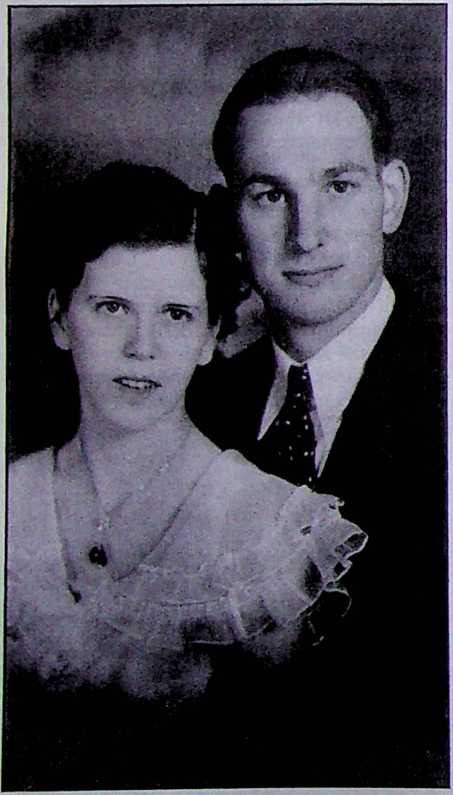

Bill mustered out of the Navy in October 1931 and returned to Clinton. He again went into government service with the Civilian Conservation Corps to head a group of 40 young recruits at Deception Pass. In 1932, he married Alice Peterson, a sister of David McLeod’s first wife. Although his work took them to several locations including Alaska, they built their permanent home on Mutiny Bay Road where they raised their two sons, Roger and Don.

After graduating from Langley High School, both boys attended Western Washington University in Bellingham. Don went to Cordova, Alaska to teach school for six years. He also started fishing commercially. Roger taught school in Oak Harbor for four years and then moved to Alaska to teach school in a native village near Kodiak. While in Alaska, he attended the University of Alaska at Fairbanks where he received his master’s degree in education. Like his brother, he also became interested in commercial fishing. He owns a purse seiner and a gill netter. In 1968, Alice and Bill spent two months in Alaska visiting their sons and their families. Both Roger and Don returned to South Whidbey Island to live.

Roger and his wife Marian have three daughters—Kara, Jana, and Sarah. They live on Saratoga Road near Langley. Don and his wife Carol, and their sons Nels, and Lars live on Bush Point. Alice Bergquist died in 1984 shortly after she and Bill had celebrated their 51st wedding anniversary. In 1985, Bill was living at his Mutiny Bay home.