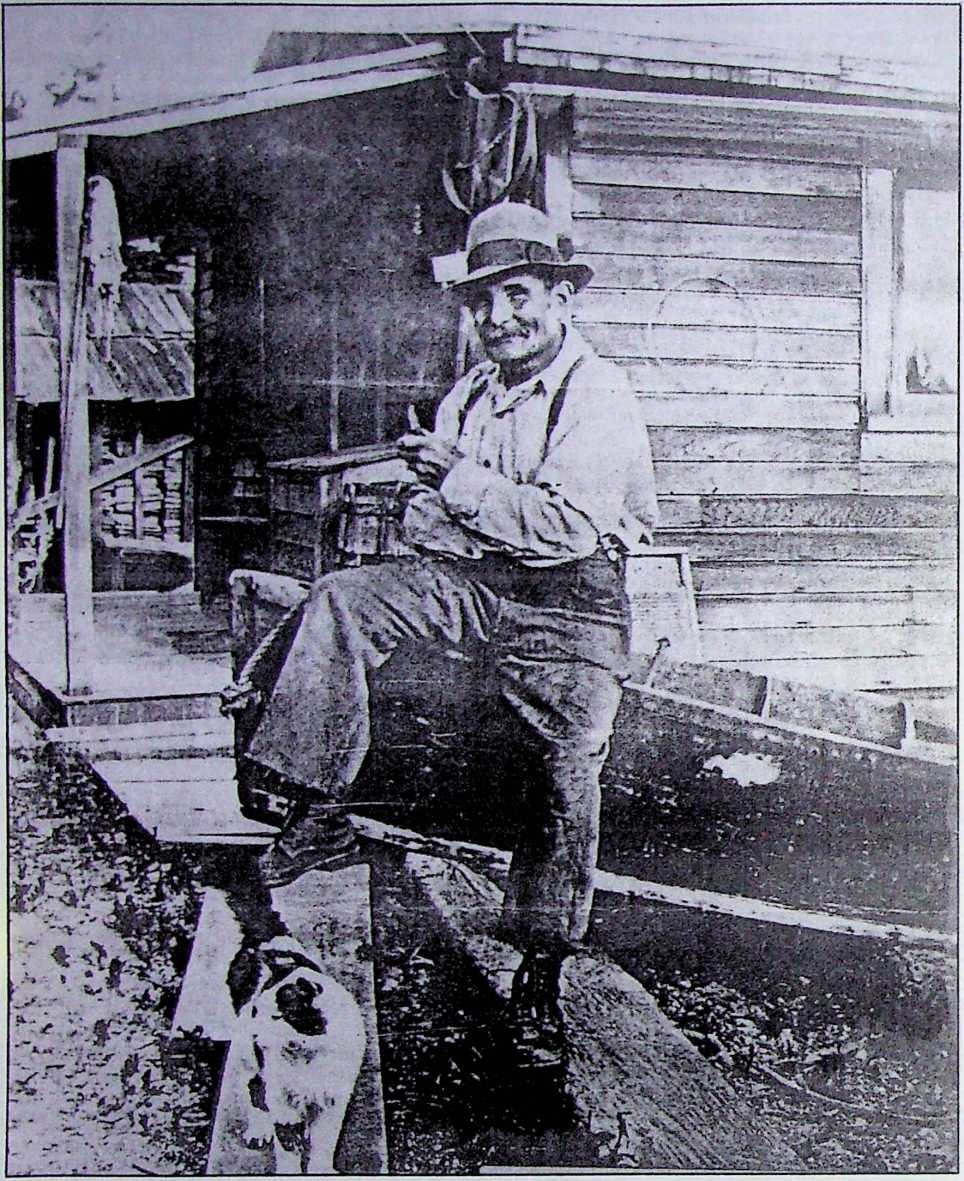

One of the most unique and best known “native sons” of the Freeland area was Austin “Deke” Marshall whose father pioneered in the area prior to 1880. “Deke” was born in Langley in 1894 and died in Freeland January 9, 1974. The Whidbey Record carried an account of him in their January 16, 1974 issue.

“Deke Marshall was not more handsome than most. He was not better known than many, or more versed in law or politics or science. He had only a small circle of close friends, and held court for them just inside the door of his store. “We first came across Deke when we interviewed him for a feature story last September. The interviews ranged over three days, consuming hours in pleasant conversation and fascinating anecdotes about early South Whidbey history and lore.

“Deke Marshall had an amazing gift of memory. Two weeks after the interviews, he quietly observed his 79th birthday: A lifetime spent in Freeland, taking mental note of what went on around him.

“Talking with him was an experience. Names, places, dates, faces: They were all there, stored in his mind and waiting to be shared.

“They wait no longer. “Deke Marshall died last Wednesday. “Quietly, just like he lived.

“Austin Marshall, native son: Bom, Langley, September 22, 1894; died, Freeland, January 9, 1974. Survivors: son Gerald, Seattle; a grandson, a grand-daughter and two great-grandchildren.

“Austin Marshall: Store-keeper, fish trap builder, radio mechanic, jitney driver, historian.

“His ‘archives’ were messy. A pile of yellow newspaper clippings, family photos, old National Geographies, and memories. His ‘library’ was his store, Austin’s Store, in Freeland since 1937. The name Austin survives on maps as the area just south of Mutiny Bay, but he was known as ‘Deke’ to most everybody.

“How the hell did you get that name,” his friend Stan McDonald once asked him. ” ‘I’ll tell you,’ he said. ‘I used to be in the woods, and they called me the Deacon.’ “

“Those who liked him called him Deke; those who didn’t called him lots of other things, but he didn’t seem to mind.

“Funeral services were held Monday at Hedgcock’s Funeral Home. McDonald was one of the pallbearers.

“Deke was laid to rest in the Langley Cemetery.

“An incredible collection of history was laid to rest with him. It was never written down, never recorded. His glimpses of life in these parts over the past eighty years or so lives now only in the scattered memories of those who knew him and heard the stories.”

From the Whidbey Record, September, 1973, by Gordon Clark.”

‘Jake Anthes had a store where Rich Clyde’s garage (in Langley) is now. It burned down in 1911. They didn’t find out who really set fire to the place, but three weeks later the other store across the street burned down. It was common knowledge then who burned out who.’

“Austin Marshall is a storehouse of anecdotes of early Whidbey Island history. He ought to be; he was born here in 1894, and has lived in the area for most of the intervening 79 years. “Marshall was born on Miller’s Marsh Road, near the elementary school. It’s Maxwelton Road now, but back then there was no Midvale, and not much Maxwelton.

“There really wasn’t much of anything, he says. He lives in Freeland now, and almost always has, watching it grow from a couple stores on the beach to the commercial center it is now. “For nearly thirty years, one of the stores in Freeland was his, called Austin’s Store. It is next to the highway; the cedar mill is his neighbor.”

‘In 1901—midsummer—D. Forrest Sandford started The Freeland Bulletin. He was the first manager of the Freeland Colony. They were Socialists, but they’d be called Communists now. They were successful, and they weren’t so bad. It’s like the stock companies now.’

“Others in that early Socialist experiment were G. W. Daniels, A. K. Hanson, and the father of Frank Hamlin, a county engineer for years.”

‘They kinda went on the bum, then picked up again . . . but they quit in 1923.’ “The colony’s store was built on a small dock about where the public boat ramp in Freeland is today.”

‘Hazen’s dad (J. Herbert Hazen, the father of the late Henry Hazen) was running the store at the dock. M. W. Shaw had been talkin’ to the wrong people, and he came in and said, ‘I want my money out.’ Well, it took Hazen about three hours to figure how much Shaw had coming.”

‘When he finally said, ‘It’s $70,’ Shaw said to leave it in then, because he only put in five dollars to start with.’

‘Shaw was quite a character. He was as radical in reverse as some people are forward.’

“Talking about his friends—and the other ornery cusses—is an obvious delight for Austin Marshal, even though most of those early men and women are now dead, and remembered as pioneers here.

“Marshall sits on a chunk of log, just inside the front door of the store, the one cleared spot among the litter of old newspapers, empty cans, and dusty bottles. The store’s stock apparently was never liquidated when he closed its doors rather suddenly in 1966. Some shelves are bare but others are still lined with cartons of Granger pipe tobacco and Riz-La papers, Crescent spices, and canned goods.

The windmill at Mutiny Bay built by Austin “Deke Marshal in 1924 provided water from a spring on the beach to the family home 160 feet above on a bluff called Sand Hill. The Seattle Times published this photo of it in 1960 looking south across the bay.

“He digs through a pile of papers and maps and pulls out a photograph of a school class, standing in front of a wood frame building. The picture is cracked and well-worn, but still clear. Austin Marshall is in it, third from the left, front row, in knickerbockers and a shy half-smile.”

‘There’s Roy Newell, and Al and Cliff Thompson. That’s Tiemeyer, the man who fell dead on the mowing machine. Fred Howard and Stella Newell. Bailey the school teacher, Benny Porter, and Old Man Lin.’

“There are fifty or so men and women, boys and girls in the photograph. The school used to be just up the beach from the Mutiny Bay Resort. It was the second school in the area; the first one still stands, though hardly recognizable. It’s the back of a house (which was built later) standing at the corner of Mutiny Bay Road and Robinson’s Road, across from Cookson’s old store. It was built around 1891.

“That old school is in the area known as Austin, so named by Marshall’s father, who filed the original deed in order to establish a post office there. That was about 1900; ‘I was just a squalling brat then,’ Marshall recalls. Note: The deed from Pioneer Title is dated July, 1902, and signed by T. H. Marshall.

“He attended the second school, but it hadn’t been built yet when he started his education. Then, the students had to follow the teacher, and she was at Utsalady, at the other end of Camano Island. The sessions lasted three months.” ‘I lost a dime up there, going to get a spool of thread.’

“A pause; and a chuckle: ‘I wonder if it’s still there, lying in the dust?’

“His teacher at Utsalady, and at the school at Mutiny Bay, was Bessie Brooks, the daughter of the Brooks of Brooks Hill Road.

“Just as he remembers the name of his first teacher, he also remembers many of the other events, large and small, that made up life in the early days of South Whidbey.”

‘I remember seeing a ship aground at Bush Point. It was the Centennial, one of the first steel hulled ships. ‘People were still saying a steel ship won’t float,’ he interjects with a grin. It was the summer of 1902, and we heard the crash. My mother gave each of us three kids a dime apiece to see what made the crash . . . The ship was hard aground, but two tugs pulled her off.’

“The other two kids were playmates; Austin was an only child. “After his early schooling, he roamed around, working at several jobs.” ‘Beginning in 1915, I worked for the Porter Fish Co. for two seasons, then one season as a pile puller and a season in Alaska. Miserable weather there. They claim it got warmer inland, but it sure didn’t on the water.’ “Austin rummages through the pile of papers and pulls out a dog-eared 1956 National Geographic map of Alaska, to show where he worked on a pile driver near Skagway. He remembers dates, names, conversations.

“He was drafted by the army for a year when The Great War exploded across Europe, but he never got out of the United States. He spent most of his time going to various radio schools.

” ‘I would have stayed in, and maybe I’d be better off, but I didn’t want to stay in.’

“Back in Freeland again, he ran a jitney for hire from Bush Point. He’d be called a cabbie, now.

” ‘Never made any money—oh, I made a good living. The trouble was tires. I bought one that lasted 300 miles; it was guaranteed for 3,500. Tires were no damn good then; they were fabric. The first cord tires were in 1920.

” ‘I remember buying supplies from Phil Simon, on the dock at Langley. A good guy to deal with.’

“What kind of car did he drive?

” ‘The only car. Ford’s Model T, of course. Everything went wrong or was backward, but it still ran.’

“The jitney service lasted four or five years, followed by a period repairing radios, and welding. This was done on Windmill Hill.

” ‘I owned 35 acres there. Should have kept it, it’s worth a half a million now. I didn’t pay much for it, and didn’t get much when I sold.’

“Austin’s Store was built in 1937, and it was a flourishing general store. At one time he had two clerks.

” ‘I had a hell of a time when the road out front was built. 1 think they started it in the summer of 1915. Before that it went along the beach on those two dikes (about where Bayview Road is now).’

“No customers have crossed the threshold for seven years. Now Austin Marshall sits among the litter and the memories, talking and chuckling over things past and present. He doesn’t speak much about his family, though. He’s a widower and has one son, Jerry, who works at Boeing in Seattle. From a stack of letters he extracts a post card from Jerry’s wife, telling about their current assignment in the Virgin Islands. The post card, though brief, closes with ‘See you when we get back.’

“Another son, Donald, was killed about five years ago in an accident on a log boom he was working out of Everett.

“Marshall’s discerning eye and perceptive wit have seen a lot of changes, from steel boats ‘that can’t float’ to men walking on the moon. While others look forward to see where we’re going, Austin knows where we’ve been.

“Names of men and women who are now known to many only as road names, were to him friends and peers.”

Austin “Deke” Marshall was nearly 80 years old when he died. His store in 1985, has become Harold’s Gay 90’s, a pizza and spaghetti restaurant with a soda fountain and candy store. Outside, the old Shell gas pump remains as a tribute to the building’s history. Inside, copies of old newspapers and photographs hang on the walls.

The original radio and auto repair shop at Windmill Hole is at Mutiny Bay not far from the restaurant’s location. The windmill there was built by Austin in 1924 to provide water from a spring on the beach to the family home 160 feet above on a bluff called Sand Hill. The Seattle Times published a picture of it in 1960 looking south across Mutiny Bay.

The original windmill had 16 hand-made cedar paddles about 12 inches wide. They were driven into a hub made of wood about 24 inches in diameter. The hub was fixed on a drive shaft of an auto differential to reduce the speed. The axle end of the differential had a bent shaft to make a crank which operated a pump. Steel bands were driven over the ends of the hub to prevent splitting, and also for a brake which was secured around the band. This was operated from the top of the hill whenever a storm was approaching.

The first bad storm in about 1933, broke the brake and threw out all the paddles. They were replaced, but reduced to eight. The second storm, the same one that destroyed the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, broke all of the paddles except one, which destroyed the tower. A new tower was built and metal blades were installed with a wire hoop around the outside. They must have been replaced again, according to Gerald Marshall, the photo taken by the Times, he said shows an entirely different set of paddles. He also noted that the windmill was built some 15 to 20 feet higher in 1924, but the bank on which it rests has eroded since then.