A Bridge Between Two Worlds: Chief William Shelton

His Story Poles and Enduring Legacy

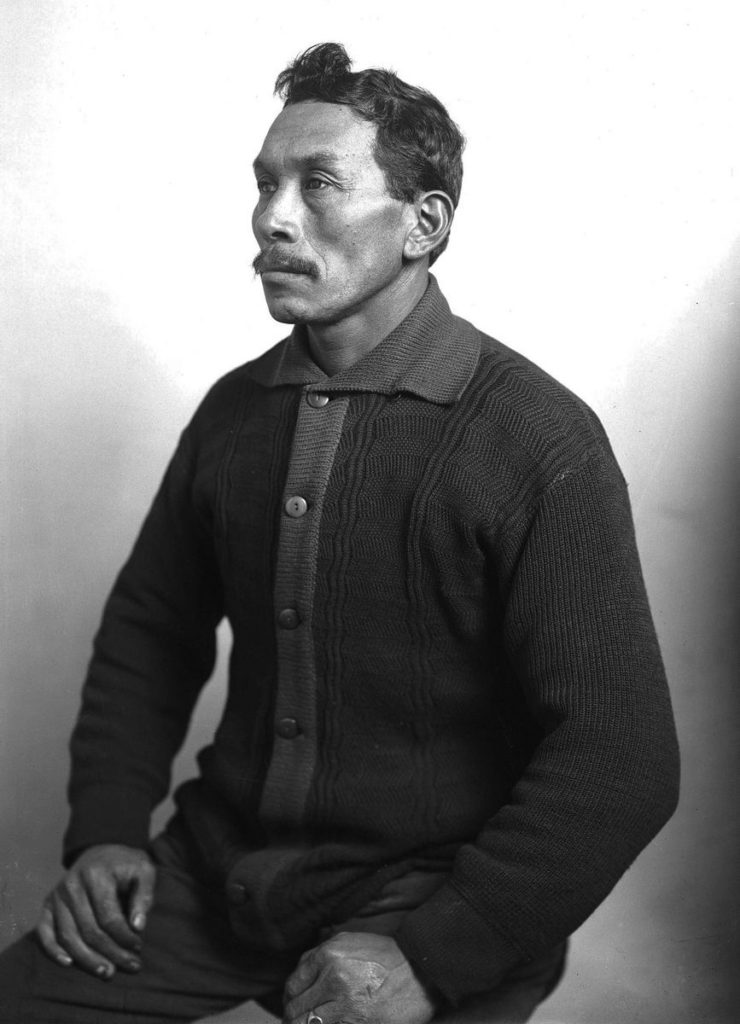

Few Whidbey Islanders know of William Shelton. He was the last hereditary chief of the Snohomish Tribe and was born at Brown’s Point (now Sandy Point) on Whidbey Island in 1868. The family lived at Possession Point, but his mother went into labor at Sandy Point and delivered there.)

Few Whidbey Islanders know of William Shelton. He was the last hereditary chief of the Snohomish Tribe and was born at Brown’s Point (now Sandy Point) on Whidbey Island in 1868. The family lived at Possession Point, but his mother went into labor at Sandy Point and delivered there.)

He was an advocate for Native Americans, a storyteller, and a prolific carver of story poles which tell the stories of his tribal legends.

Growing up, Shelton listened to the elders that were present at the Point Elliott treaty signing in 1855 at Mukilteo. Tribal leaders of the Snohomish, Snoqualmie, Skagit, Suiattle, Samish, Stillaguamish Tribes and allied bands living in the region debated for ten days prior to the signing.

They knew white settlers were going to change the way of life for them. They also knew that if it came to war, it was something they could not win.

They did want to learn the language and the working trades of the white man. Medical services and schools were another need. The promise of large tracts of land, and the ability to fish and hunt as they had been accustomed to was also promised in exchange for land. Some tribal leaders, though, were concerned that they were giving too much for so little.

On January 22, 1855, the treaty signing took place. Governor Isaac Stevens gave a glowing speech in English which was translated into Chinook, a trading language used by local tribes.

The treaty was drafted by the government with no input or negotiations with the tribes. Most tribal leaders signed the treaty with a thumb print. They were not paid in money for their lands, but in blankets, clothing, and farming implements, and promises of reservation improvements.

As a child, Shelton remembered visiting a potlatch house at Scatchet Head Bay (Cultus Bay) with large timbers and posts with numerous carved totem figures.

During a tribal gathering at Sandy Point (near Langley) for a great feast or “Sway-gway” young Shelton saw totem figures carved inside the large potlatch house. He asked his father to explain the meanings of the figures on the house posts and was told that each carving represented a story and each story carried a lesson. Before a little boy could become a great man, he would have to learn all the lessons. Shelton told his mother and father that he wanted to become a great man. From that time on his parents taught him the stories.

During a tribal gathering at Sandy Point (near Langley) for a great feast or “Sway-gway” young Shelton saw totem figures carved inside the large potlatch house. He asked his father to explain the meanings of the figures on the house posts and was told that each carving represented a story and each story carried a lesson. Before a little boy could become a great man, he would have to learn all the lessons. Shelton told his mother and father that he wanted to become a great man. From that time on his parents taught him the stories.

“They told me stories which would create in me the desire to become brave, and good, and strong, to become a good speaker, a good leader, they taught me to honor old people and always do all in my power to help them,” wrote Shelton.

At age 18, Shelton ran away from home to attend the Tulalip Mission school where he was taught to read and write. He remained there for three years until he was given a position at the Tulalip Indian Agency.

Life on the reservation after the treaty was fraught with unmet promises. Education and health services were slow to come. The federal government also made a conscious effort to destroy Native American culture.

Dancing, drumming, speaking in the native tongue were against governmental rules. Shelton and older Indians questioned why settlers from across the Atlantic could keep their culture when they were being denied expression of theirs.

Shelton went to Dr. Charles Buchanan, the Tulalip Agency resident physician and superintendent of the boarding school and said, “We would like to begin again. We would like to have a day where we could all gather together – the older Indians – and have them sing old songs and beat the drum.”

Shelton went to Dr. Charles Buchanan, the Tulalip Agency resident physician and superintendent of the boarding school and said, “We would like to begin again. We would like to have a day where we could all gather together – the older Indians – and have them sing old songs and beat the drum.”

Buchanan simply told him, “No you can’t. That is against Department of Interior regulations which say no drum beating and no Indian dancing.” Tribal members were jailed for carrying out ceremonial gatherings.

The agent told Shelton to write a letter to the commissioner of Indian affairs and the Secretary of the Interior and ask for these rights. Shelton was not a skilled writer and struggled with grammar and punctuation, but never-the-less sent the letter.

Then, came the reply. It said, “The Indians could have a Treaty Day for one day and evening. They are not to dance all night nor until daybreak. They are to go home and take care of their livestock.”

Treaty Day was held in 1911, 1912, and 1913 at the Tulalip Indian School. In 1914, the government gave permission to build a longhouse.

William Shelton cut the lumber at a sawmill on the reservation. The longhouse, also known as a potlatch house, was the traditional place for Indians to meet. They came in canoes from all over Puget Sound for Treaty Day. There was dancing, drumming and speeches in the native language. Older Indians talked about being present at the signing of the treaty.

In a speech by Shelton he said, “This is not a celebration; it is a commemoration, because the Indians were not having a good time when they met to discuss and sign the treaty.”

With the longhouse completed, the Tulalip Improvement Club was created.

Here tribal members met and could discuss the issues that faced them. The older ones spoke in their native language (Lushootseed) while the younger ones spoke in English.

Shelton’s argument for calling it an “Improvement Club” was how could the government stop them from meeting if they were trying to improve themselves. Issues concerning upkeep of the reservation like roads and cemeteries were discussed.

They also raised questions about their treaty rights. One frail elderly man, who was at the treaty signing, said, “I received a fish hook and one yard of narrow red ribbon. That was some big payment for giving up my share of the land.”

The club did not meet during World War I, but resumed afterwards and kept formal minutes. Gradually, most of the language spoken was in English.

During these years, they became more vocal about issues of medical services, fishing rights, corruption of payments to tribal members, and keeping their culture alive. Using the treaty as a starting point, they began to assert their legal rights.

As Shelton worked in the Tulalip Indian Agency, he became more proficient in reading, writing and speaking English. He also developed his skills as a woodworker by working in the sawmill.

Shelton became acquainted with local businessmen in the area including Roland Hartley who would become governor of the State of Washington.

Here was his opportunity to tell the story of Puget Sound Native America. He began to carve story poles. He did this for the rest of his life. They told the stories, lessons and legends which local children learned from a pole rather a than book.

In the stories birds, fish, and other animals converse in one tongue. They taught children to be brave, loyal, and truthful and to illustrate that evil comes to wicked people and only the good prosper in the end.

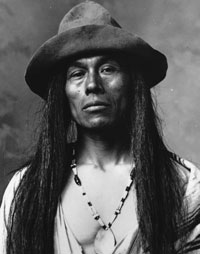

With daughter, Harriette, William Shelton would regularly be featured at local civic events such as the Coupeville Water Festival. There, they would demonstrate native dancing, singing, drumming, and storytelling all to revive and teach native culture. They would also go to schools throughout the region.

Shelton would regularly show up in native costume with full headdress and was always introduced as Chief William Shelton. The costume and headdress were not typical of Puget Sound Native Americans but more the dress of Indians from the Great Plains.

When asked about it, Shelton would say, “If we are going to fight for American Indians, we need to look like Indians. The only Indians white people see are in the movies and we need to look like them.”

William Shelton died in February 1938. At the time, he was carving a story pole for the Capital grounds in Olympia. That pole was later finished by other carvers and erected in 1940. It stood until 2010, when it was taken down because of its deteriorating condition.

The remains of that pole are being stored at the Hibulb Cultural Center.

His daughter, Harriette Shelton Dover, carried on her father’s work fighting for American Indian rights until her death in 1991 at age 86.

–Article by Bill Haroldson with assistance from Tessa Campbell, curator at the Hibulb Cultural Center located at 6410 23rd Ave NE in Tulalip, WA.

To become a member of the South Whidbey Historical Center, click here: http://southwhidbeyhistory.org/join/

Here is an excellent video about William Shelton in a video produced by Quil Ceda Media.

William Shelton and the Sklaletut Pole from Quil Ceda Media on Vimeo.