Anders, Ester, Albert and Bertine Anderson

“If we had 50 chickens how many eggs do you suppose they would lay per day and how much money could we get for the eggs?”

Anders Anderson was sitting at the table after dinner doing arithmetic. He didn’t really expect his wife, Bertine, to answer. She had heard him ask questions like that before. That particular night she surprised him, pausing in the midst of clearing away the dinner dishes.

“Anders, you know you didn’t come all the way from Sweden just to spend the rest of your life working in a Montana mine smelter. Every night you fiddle around with a paper and pencil and fuss about how much you want to get out into the country. Stop dreaming and do something about it!”

That’s how it came about that Anders and Bertine Anderson packed up their belongings and their year old daughter, Ester, and took the train from Great Falls, Montana, to Seattle in 1906. Their daughter, Ester Anderson Moe, who lives in Clinton as this is written, was inter-viewed by Eva Simmons and gave the following account of her family’s experiences in Langley.

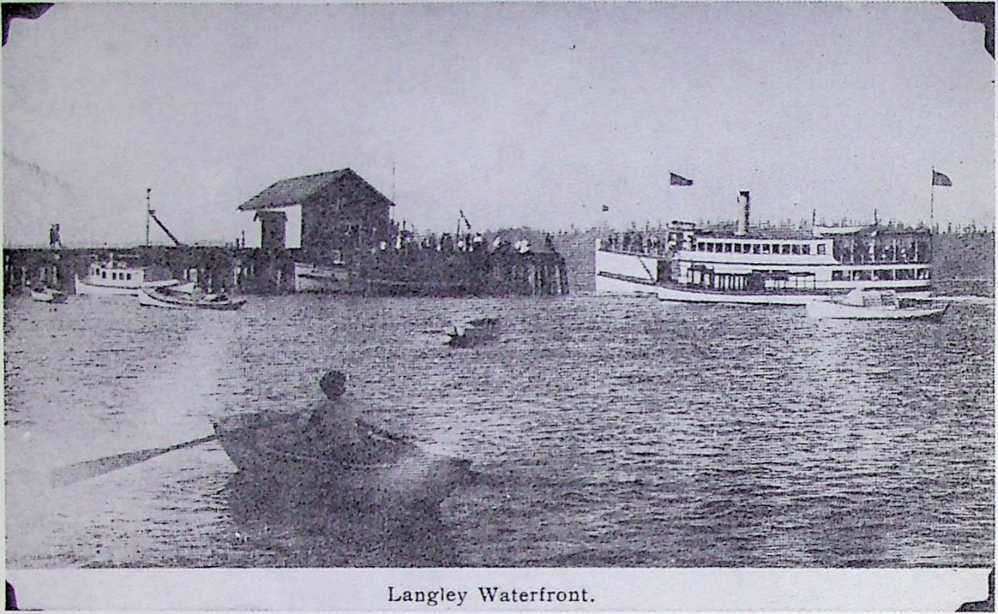

“My parents didn’t know anything about Whidbey Island except that it was being advertised by Jacob Anthes who was running a boat between Seattle and Langley. Dad took the boat trip and investigated the property that was being advertised for sale. He bought 20 acres a mile and one half south of Langley on the road that now bears his name.

“In October, 1906, when I was one year old, we moved to Langley and lived at first in a two room house on Second Street located on what is now the parking lot for the South Whidbey Record office. Father started building a two room house on the property he had bought and we moved in a few months later. “We lived next to the cemetery. Dad dug graves— made a few dollars. I followed him as he worked. I saw it all. I really knew what a cemetery was all about. I watched him dig the holes, put the wooden box down, and I saw the tears and I saw everything. I was there when he covered it afterward. I was only two — but never was afraid of cemetery — because I knew everyone else was. I was very young when I realized this life wasn’t our permanent home — that there was something beyond that. And I think it has made a little influence on my life — which I think is a good one. There was a road around the edge of the cemetery — and I wouldn’t go there for anything. But I’d go to visit Kings who lived at junction of Clinton and Maxwelton roads, and I’d stay till all hours of the night, and I’d walk home through the cemetery — guiding myself by the tombstones — because I knew nobody there would hurt me. I knew where everyone was buried.

Memorial day was one of the biggest events in the Anderson household because people from all around who had loved ones buried in the cemetery would come to visit the graves. Since the Andersons had no relatives nearby, all of them being in Sweden and Norway, the folks visiting the cemetery became, in a sense, the Anderson’s guests. Ester describes the situation.

“All year we had been saving up the lard buckets. There was no water in the cemetery and folks would depend on us for water and containers for the flowers they put on the graves. By the time people would get off the boat at the Langley dock and walk the two miles to the cemetery they would be hot and tired. Mother had been baking all the previous week and the folks would stop for water. We had a good well with a windmill attached to give running water but folks also would sit and rest and enjoy some of mother’s sweets and coffee.

“Some of the folks who came couldn’t remember where their family’s graves were. I thought I was the smartest thing! Only three years old and I could tell them where everyone was buried. I was there when each grave was dug.”

“Father never did have the big chicken ranch he had dreamed of. He did some logging, worked in the brush camps and sometimes worked in Snohomish or LaConner for several weeks. One year we planted strawberries but the weevils wrecked the whole crop. We also grew blackberries and loganberries. We had pigs and mother made head cheese, blood sausage and pork chops. She had a huge crock which she would fill with pork chops covered with grease to preserve them and we would have meat all winter. We also had bins of potatoes, carrots, apples and home canned goods in a cellar under the house.

“Father didn’t believe in charge accounts. The only thing he ever charged in his life was his land. One special occasion I’ll never forget. Each day I’d walk to Langley and pick up the mail and then go home. This day I needed a pencil. Will McGinnis was in charge of the general store and I told him I needed a pencil but didn’t have a nickel. He said to take the pencil and bring the money the next day. When I got home my father asked me where I got the pencil and I said at the store. He asked me if I had paid for it and I said no. He said, ‘Don’t ever do that again. If you can’t pay for something do without it until you can pay for it.’ I never forgot what he said. Years later when I became Postmaster I needed some furniture in the worst way. I decided to charge it and went to Sears in Everett and bought a davenport and a couple of little tables. I suffered and worried so over that! I’ve never charged things since. Our family has the oldest bank account in the Langley bank that has been kept up continuously up to the present.

“In 1915 the bank went broke. I had $15 in it. I remember how I cried. I thought the end of the earth had come. My father had given my mother $40 and told her to send to Sears and get a new suit for herself. She said she would put the money in the bank and send for the suit later. That was on a weekend when he came home from Everett. Monday the bank went broke. Finally father gave mother $40 again and, Boy!, she sent to Sears right now! I remember it yet, the prettiest green suit and blouse.

“The place I loved to go in Langley was “Blackie” Anderson’s blacksmith shop which belonged to my friend, Alma’s father. The forge would be going and people would be bringing in their horses from all around. The women would go to Mrs. Anderson’s house to wait while the men- folks were getting the horses shod. Mr. Anderson had a little room in back of his shop with a cot, a stove and always hot coffee for the men. He had peppermint candies, too, and a fish picture. It was warm in there. You could eat all the peppermints you wanted while he sat and told fish stories. I loved him. For many years I thought he was my father’s uncle because of the same name. We always celebrated holidays together. I felt terrible when he died.

“There was a man in Langley who used to get drunk and when he did he was really bad. When we first came to Langley and I was real small we were living across the street from “Blackie” Andersons. On this particular day Mrs. Anderson came running to our house crying that this man was trying to kill Mr. Anderson, my friend Alma’s father. He thought his family was hidden in the Anderson house and he shot through the wall. It was awful! There were lots of houses and businesses all around and a crowd of people began to gather. Everyone was scared. His family was scared too, and hiding in different places around town. Ted Howard and my father followed this man and all at once we heard shot after shot ring out. Everyone wondered what was happening. Father told us afterward what occurred. He had said to the man, ‘Let’s have a race and see who can shoot the highest’. The man had had just enough to drink that he thought that would be fun, so they were all shooting up in the air until the bullets were gone.

“March, 1916, was known as the time of the “big snow”. It started to snow in the afternoon while we were all in school, great big snowflakes, and kept on coming down all night. That evening I sat by the window watching the big flakes. I didn’t want to go to bed they were so fascinating. When we woke up in the morning there were three feet of snow on the ground. I wanted to go to school but father said no and instead, he rigged up some kind of sled with a sort of plow in front to push the snow away. He went up and down the roads and to Sandy Point clearing a passage way and we missed only one day of school The snow stayed on the ground forever! We built forts but I hated it because the boys made snowballs and put ice in them.

“The year of the big influenza epidemic my father was working in town and everyone where he worked had to wear a gas mask. My brother became very sick and I was scared. Langley was fortunate in having Dr. Barry at that time; he had been a doctor in the Mexican war. During the flu epidemic he worked day and night and only two people in Langley died of the flu. My mother wanted to go and get Dr. Barry when my brother became so ill but I was afraid to be left alone with him for fear something would happen so my mother stayed with him and I took the horse to go for the doctor, who lived in a house at the foot of the hill on Anthes Street. I got as far as the top of the hill, and looked down and saw Dr. Barry starting to leave in a great big car.

“I screamed that my brother was dying and to please wait. I thought he hadn’t heard me but somehow he did, and he waited until I reached him. He took one look at me and said ‘you are pretty sick, too. Wait here.’ So I waited. He went into his house and came back with some medicine which he prescribed for both my brother, Albert and me. Going home I became so dizzy that I fell off the horse but I managed to get home by leading the horse.

“There were different effects from the flu and I had the kind where you get the nosebleed. My nose kept bleeding and we couldn’t stop it. My mother came with a basin and stood outside the door and cried. So much blood was drained away from my head that I couldn’t think clearly and I started to sing, “Nearer My God to Thee’’, and all kinds of hymns. Eventually I recovered but losing all that blood did something to me. When I was able to start back to school which usually took only 10 minutes to walk to from our house I could only go a little ways without stopping to rest on a stump. Every year for several years at the same time in November that I had been ill I would get the flu.

“We used to have all our school plays including our senior play in the Dog House. Also we had track meets and would compete with Coupeville. We would go there in an old truck with benches along the sides. We high school girls had a neat drill team and we would get all dressed up in blue pleated skirts and white middies with lots of bows in our hair but by the time we got to Coupeville in that truck we would be covered with dust. One time we went by boat to Coupeville, a much better way to travel. We had a neat drill team and would perform at meets. Ruth Anderson Heggeness could jump higher than any girl in Island County.

“Only three pupils were in my graduating class and Evelyn Spencer, the County School Superintendent, was the speaker. Graduation was on a Friday evening. The next morning Phil Simon took a large group of us in his two commercial boats to Hat Island for a picnic.

“We landed on the northwest corner of Hat Island and Nell Harmon and I decided to walk around the island. On the side facing Everett we saw a stream and decided it would be fun to follow it, thinking it was just a short ways until it came down on the other side. We walked and walked all day long. We had been going in circles but we finally came out on the Clinton side of the island then headed north. Our skirts were pulled to pieces by underbrush, my feet hurt and there was nothing to eat. Worse yet, a bad storm came up. Finally we came upon the cabin of an old fisherman who had a few chickens, a garden and an apple tree. He was so nice! He boiled us a big kettle of potatoes and several eggs. The potatoes tasted so good, but I wouldn’t eat the eggs because I thought they might be old.

“We waited quite a while until he thought the storm had calmed down enough so that he could take us home in his boat. He got it started but it almost capsized so we went back to the cabin and waited some more. Eventually we started out again but the current was so strong that it carried us to Camano Island instead of Langley. In the meantime Phil Simon had taken the first boatload home to Langley and had come back for us but couldn’t find us and had returned to the Langley dock where a lot of worried parents had assembled. They saw our boat start out but when it disappeared behind Camano Island they thought we had capsized and drowned. When we finally landed on the east side of Camano Head we discovered three men on the shore who were looking for another party that had actually drowned. They phoned Dell Smith who had a tug-boat on South Whidbey and he rescued us. When we landed I had to walk two miles home. We didn’t have a phone and my mother knew nothing about what had happened. She was asleep when I finally arrived.’’

After she graduated from high school Ester attended Bellingham Normal school, then returned home to teach in the Deer Lake Consolidated school, living in the teachers’ cottage nearby. The teachers cooked their own meals, split their own firewood and used produce from the garden of the owner of the cottage. They packed their noon lunches and ate at school. Drinking water was from a bucket with a dipper used by all. A janitor cleaned the school building and started the fire each morning. Ester was amazed to find the double desk she had used as a child in Langley grade school in use at the Deer Lake school. Her initials were on one of the desks. The Langley school had purchased new desks and their old ones had been sent to Deer Lake and Maxwelton schools.

Of her teaching days Ester recalls that they had an excellent PTA and the parents, teachers and pupils combined to put on many programs and plays with these events usually held in the Clinton Progressive Hall. One play she will never forget, “In the Light of the Moon.” Her account of the incident follows.

“While they were practicing one night a stranger came into the hall — he was from New York — and was camping down on the beach at Glendale. He knew all about lighting — and the players needed a special-effect for a scene, and they didn’t know how to get it. He rigged up some lights — and it was just beautiful — the way that light shone on the floor. I don’t know what we would have done without him. None of us were real directors — just helping out. He was really something. So he directed this and we were real glad to have his talent. About 3 days later, the Glendale post office was robbed — and he’s the one who robbed it! The post office was in the store. They caught him quickly — in Portland — trying to cash a money order.”

Anders Anderson died in 1943 and Bertine in the mid 1970s. Their son, Albert, married Mildred Hegglund, daughter of a well known local family and they took over the home place. Albert and Mildred also purchased several other sizeable acreages in South Whidbey. Besides operating their farm they also were the owners of one of Langley’s leading grocery stores, The Big Penny located on Anthes Street on the site of the present Good Cheer building. Albert died in 1982. Mildred still resides in the home place as this is written.

See more info about Ester Anderson Moe on this site.